It’s hard to say what astonished me more: the Polish naiveté regarding fundamentals of capitalism, or the speed with which Poles learned their sometimes painful lessons in free-market economy. For example, the notion that a product’s price must exceed its cost of production seemed entirely foreign to their minds. Who could even tell what the cost of production was? Who kept accounts? Who considered consumer demand? Who had heard of a marketing survey? And inflation-deflation? Poles naively assumed that inflation was the sole option: prices only increased, the value of the złoty only decreased. Buy an infinite supply of whatever the market made available while prices were lower than they would become; convert all your money to hard currency, and hide it in a teapot. For their part, producers assumed that the buying public had an almost infinite capacity to absorb whatever goods a merchant could provide, at virtually any price he set, quite independent of such considerations as competing goods and services, the laws of supply and demand, and the general atmosphere of the shop. Everyone assumed that anybody who stooped to go into private business would automatically become wealthy.

But in 1990 Poles learned that the value of the dollar against the złoty could actually drop, and that savings put in złotych accounts at 50% interest out-performed savings stashed in the teapot. That prices might drop as well as rise. That goods could become so plentiful as to make lifetime stashes cumbersome and unnecessary. That the market would not absorb whatever commodities a supplier chose to throw at it, at whatever prices he set. That not all capitalists become rich overnight. That an attractive shop offering friendly service might make the difference between success and failure.

That even in a capitalist economy, failure is possible.

Poland’s venture into capitalism was far enough along by spring 1991 that several private shops had already failed. Intermak sticks most prominently in my mind, a multi-roomed, privatized yuppie shop when it opened, complete with red awnings and a row of banners hung from light posts all up and down the sidewalk and a stylized western-style logo. Its clean, bright windows were filled with cartons of pasteurized (French) milk, packaged (German) cakes, tins of

Mövenpick tea. For a few months it was the talk of downtown Łódź. But Intermak’s location was just a bit out-of-the-way, and soon more conveniently situated shops on Piotrkowska stocked identical products. The owner apparently tried to leapfrog ahead of his competition with a frozen yogurt machine, but this proved one jump too far for Łódź in winter 1990-91. So there was a period of brave front, when the shop stayed open and well-dressed sales clerks gazed idly out its windows at passing non-customers, and then there was the period of locked doors with a sign on the window, and now Intermak sits quite empty, its fading red banners a potent reminder that all that rises does not necessarily reach the heavens.

But my purpose is not to speak of failures, it is to focus on three commercial successes not in wealthy, cosmopolitan Warsaw, not in touristed Kraków, but in the working-class city of Łódź. Three cases of entrepreneurs walking, as it were, off the edge of conventional communist economic wisdom, learning a few tough lessons and grasping a few basic principles, and flourishing. Here are three different businesses, three different stories, three different reasons for success (at least to spring 1991), each proof that there is money to be had in Poland, even in depressed Łódź, and you do not have to run off to Britain or America to Make It.

The first of these enterprises is perhaps the simplest: a private grocery which opened at the corner of Północna and Mariana Buczka (since 1990, Aleksandra Kamińskiego) not 200 steps from our flat. With all the fanfare of a new coat of paint and steel grills over the windows, this shop opened in the spring of 1990, when many private groceries were opening, including one half way around the block. It flourished for three simple reasons.

First, it stays open longer on more days of the week than competitors. Michelle and I nicknamed it “The Seven-Eleven Spożywczy” because of its hours. We, and others in the neighborhood, spent a lot of money there when other shops were closed.

Then the owner struck on two ideas which were to make his fortune: beer and video cassette rental. At first he sold only one brand of beer, Żywiec, a good Polish beer hard to find in Łódź, which, by driving frequently to the brewery south of Kraków, he managed always to keep in stock. Neighborhood beer-drinkers drank prodigiously, conditioned by the Polish axiom, “Nothing good lasts very long.” Gradually they learned that the beer would always be there, and their appetites abated. Still, this store is the neighborhood beer center in a neighborhood which, thanks to the soldiers’ hospital and the army medical training center, consumes a lot of beer.

The owner’s venture into video-rental was equally successful. You walked into the store for a loaf of bread or a few bottles of piwo, and on the screen of his TV-VCR you saw Sesame Street or the Smurfs or some grade B western, and you just naturally stopped to watch, check out rental fees, and maybe head out the door with a couple of tapes for the wife and kids. Whether the owner conceptualized this combination of groceries and videos himself, or borrowed it from some U.S. Stop-and-Go store, I don’t know. However, the combination made his fortune, nearly crowded out all other commodities, allowed him to restrict his hours and let him hire a bunch of clerks to do his work for him. If he advertises at all, it is with a simple board hung on a telephone pole, bearing the single word PIWO.

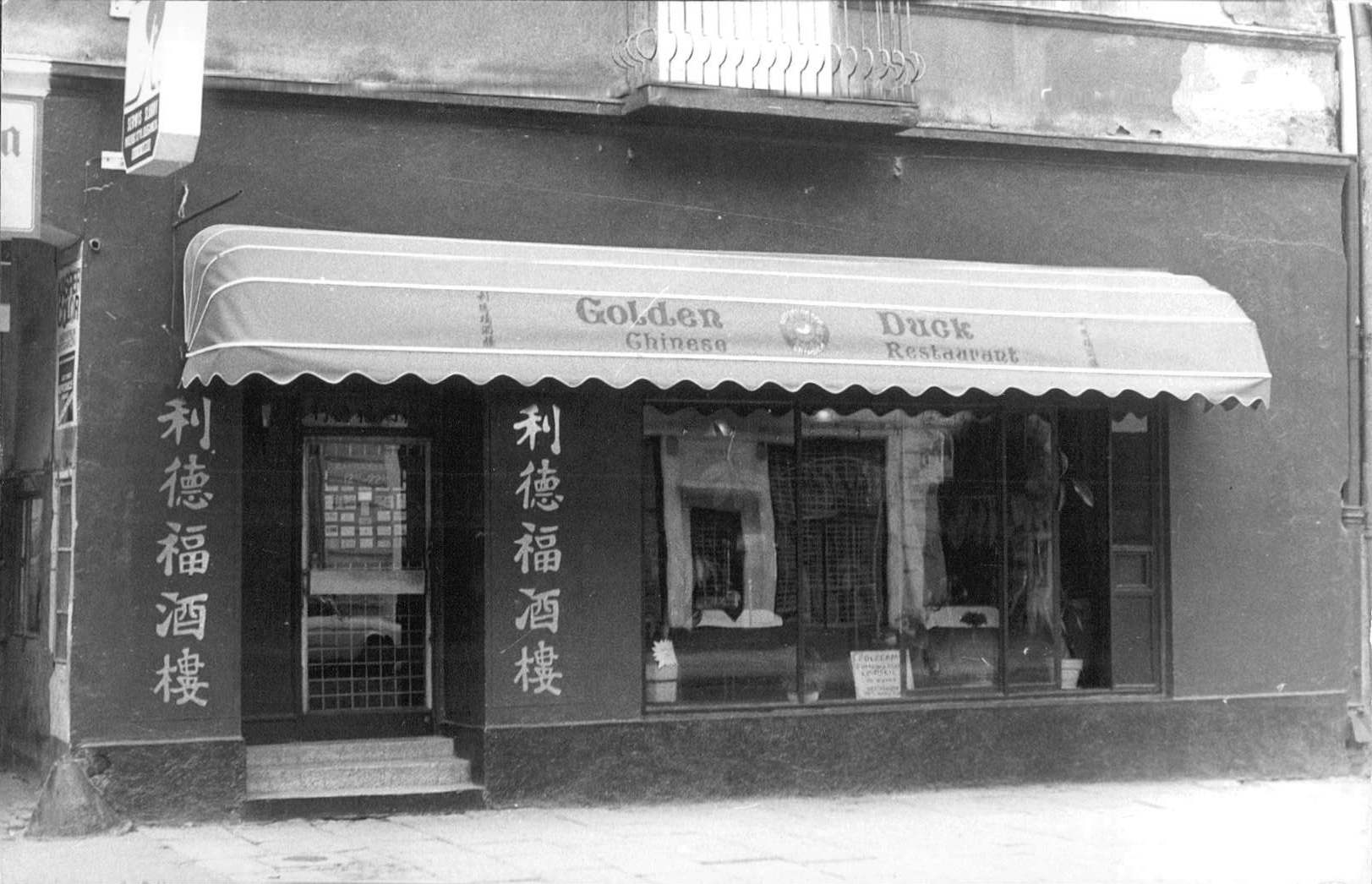

The Golden Duck Restaurant, 79 Piotrkowska, is a different matter entirely: class operation all the way, no drunks hanging out here, wine preferred over beer, although you can order western beer in aluminum cans with dinner. A red awning with rich golden letters—English, Chinese, very small Polish, there on the logo—identifies the establishment, which, being just down the street from the Grand Hotel, attracts a lot of foreign visitors. The Golden Duck today offers a rather extensive menu in Polish, German, and English; waiters in black suits and white shirts who give good service and speak several languages; and take-out service available at a 10% discount. Diners sit on plush red seats, at tables with elegant white tablecloths covered with deep red napkins. The usual Chinese bric-a-brac comprise the interior decor, with black and gold lanterns, live rubber trees, wall paintings. A vase of flowers adorns each table, and a bouncer guards the door.

When first the Golden Duck opened, Michelle and I often dined there alone. Poles were generally unfamiliar with Chinese cooking, and waiters advised customers the pork was going to arrive cut into small bits, not in one large Polish brick. One evening when Michelle was finishing a can of beer, two small boys snuck up to the table, asking if they could have her empty can to collect the deposit. The owner himself chased them off. Seats were plain, the menu was one language only, and as often as not only a couple of “Chinese” dishes were available. We sympathized with the owner’s problems in keeping a restaurant functioning given the then-chronic Polish food shortages, and because we were thrilled to have a more or less genuine Chinese restaurant in Łódź—and because dinner at the Golden Duck then cost only a few bucks apiece—we ate there often, bringing friends whenever possible.

When we returned to Poland in the fall of 1990 after summer abroad, the owner had a surprise for us: he had privatized the restaurant. Elegant red-and-black paper napkins had been printed, and gold-and-black business cards. No more boys hustling aluminum cans. Redecorated interior and a new menu. Larger portions and slightly larger prices. Noticeably more customers, as the doors of Łódź continued to open to the West, and German and Austrian businessmen sought alternatives to the heavy Polish cuisine at the Grand Hotel. One night I overheard an Austrian tell the waiter, “I have had the duck and the chicken my last two nights here; now I want you to recommend something else.” If the Grand Hotel ever wakes up and upgrades its restaurant, the Golden Duck may be in slight trouble, but by then Łódź will be a thriving hub of international commerce. The owner of this restaurant passed a critical threshold somewhere in the fall of 1990, and he appears set for quite some time.

What made the Golden Duck was a combination of its excellent location (coupled with the increased foreign interest in Łódź), the owner’s insistence on quality, and his two years’ experience in London at various Chinese restaurants, whose business cards can be found posted on the front door of the Golden Duck. The man knew his business, bet on a new, western-oriented Łódź, picked his clientele, and won the gamble.

Jet Tours/Rainbow Tours does not sell beer, and its location—up the street from the Grand Hotel and the (once) internationally famous Roszkowski Confectionary—is not entirely convenient. Except for a few turquoise, yellow, and lavender flags proclaiming “Jet Tours,” you would not know this place exists, frankly, because it’s tucked back in one of those court areas off a side street off Piotrkowska. Jet Tours advertising took the form of a large billboard (oil paint on canvas stretched over a steel frame, standard Polish advertising sign) located first at the very busy intersection of Piotrkowska and Piłsudskiego, then at Fabryczna train station. Jet Tours is the house that advertising built… with help from the utterly inadequate, state-owned Orbis Travel Agency, and the general opening up of Poland the West.

Sławek Wiesławski, general manager of Jet Tours, is still technically a fifth-year student at the English Institute, but he, like his colleague Grzegorz, has put his studies on hold to devote full time to the business. I remember vividly the founding of Jet Tours, thinking maybe I should help bankroll this venture in capitalism, hesitating, deciding finally I would support it in the best way I could: by having Sławek handle all my international travel… not a difficult decision, really, since I had not once visited the Orbis agency and come away with anything close to satisfaction, let alone tickets for an airplane flight. Pan Am was also arrogant, American Airlines had not yet arrived on the scene, and Lot was just Orbis with another name and bureaucracy. So Jet Tours handled our flight arrangements, and the arrangements of other Fulbrights I recruited, and a very difficult time they had of it in those days.

In the early months customers paid for air tickets in hard currency only. The actual tickets had to be bought in Berlin. Twice each week, Sławek and Grzegorz drove their battered Fiat from Łódź to Berlin and back (ten hours each way, even with a minimal delay at the border), carrying with them several thousands of dollars, returning with airline tickets for their clients. There was no other way. Once I accompanied them, tending the car as they scouted services and connections at Tegel Airport, fending off a German cop who drove up all hot to bust this illegally parked Polish Fiat, then turned polite as pie when I flashed my American passport. That journey remains one of the great epic odysseys of my life, an exercise in improvisation in the teeth of one roadblock after another: hostile border guards, hostile airport officials, hostile cops, hostile Berliners on both sides of the wall. I can’t imagine making such a journey twice monthly, let alone twice each week.

And I remember the opening of Rainbow/Jet office, remember thinking how new and pristine everything looked, wondering if this venture was really going to fly.

It’s hard to get into the place these days (larger offices are being renovated in a new location just off Piotrkowska). The office looks as if a political campaign was being run out of it: notes everywhere, papers heaped on shelves, desks a mess—business, business, business. Sławek and Grzegorz, of course, no longer drive to Berlin to pick up tickets, and with the newly unified Germany and reconfigurations in airline schedules, it’s just as cheap to fly trans-Atlantic out of Warsaw as out of Berlin anyway. Jet Tours has patched into American Airlines’ computer network, and can make reservations all over the world. It can book flights on Lot, Delta, American or even Bulgarian Airlines. It can book reservations on the night ferry to England, one of Sławek’s coups: “I requested just a few tickets a year ago, but P and O Ferries said they needed some big agency like Orbis. I got nothing. Then a couple of months ago, they phoned me, asking if I was still interested. I asked them about Orbis, and their only response was, ‘confidentially, the people at Orbis didn’t know what they were doing.’ This we already knew. Anyway, they offered me several tickets at quite good terms, really. We use their ferries for the bus trips to England.”

The bus trips—the Rainbow Tours end of the operation—are this office’s greatest success: 30 hours by bus, direct from Łódź to London. $125 round trip, which for Poles is quite cheap, and easy access for trading or work. All my students from the English Institute book their summer transportation to England at Rainbow Tours. “It helped when Germany reunified and we had only one border to cross,” Grzegorz tells me. “And then we had a big upsurge in business when Germany allowed Poles in visa-free.”

“If England ever allows Poles visa-free entrance, this operation is going to be a gold mine,” I observe.

“It already is,” he tells me confidentially; “in July we are sending eleven buses to London in one week.” Multiply that out, at 52 seats per bus, and you will understand where Sławek found the money for a new flat and a new car, why he and Grzegorz are content to shelve their English studies, why Sławek’s wife Agata is pleased as piwo to work her tail off here, why the couple has not had a prolonged holiday in over a year.

Something in me takes great vicarious pleasure in the successes of these enterprises, each so close in its own way to my life in Poland. I cannot really claim to have played any role in their success, except to applaud from the sidelines. However, I also sense a loss of that Old Poland that at once enchanted and maddened, the loss of Difficulty and Inscrutability, the loss of my status as Special, the loss of innocence. Something’s gone and something’s gained, as Joni Mitchell once sang.

But in balance I am more than happy for the New Poland, and for the small part played in it by three entrepreneurs in Łódź who have made it.