“Rock Jarocin 1991” reads the T-shirt, black on white or white on black. It costs $3. Small only, this being the third day of the festival, but the woman does have two XL in a loud shade of peach. I buy two of those (they fit; the smarter black-and-white models will be of no use to anyone over the age of seven), and tuck one into my shirt and give the other to Agnieszka Jabłońska, my companion at this the eleventh annual Polish Rock Festival, and I wish I had brought a few more złotych, because there is a very nice Sting T-shirt for $6 that daughter Kristin would just love, and where in the States can you get a Sting T-shirt for that kind of money, but I blew my wad on tickets—$6 apiece—and ice cream and the train from Poznań to Jarocin, so Sting will have to wait, but I should be happy to have these two peach beauties, and let’s get on with the music, and the seeing and being seen, and the scene in general.

It’s a small town, Jarocin, and the festival quite overwhelms it. On the ride over, Agnieszka and I worried about finding the music, but amplified sound could be heard even before our train stopped, bouncing off brick and cement walls, emanating vaguely from the far end of town, by the football stadium. Her friends had fretted about thieves and hooligans, but cops are everywhere, beginning at the station, thickening toward the town center, thinning out toward the concert site (maybe they are in plain clothes there). Anyway, you want to get to the music, follow your ears or the line of policja away from the tracks, around one corner, into center city past an unmemorable market square festive with “Rock Jarocin 1991” banners, past the truck selling bottled soda pop and cartons of fruit juice, toward the lights, toward the noise. On your way, study the Polish Punkers in their Mohawks, black leather jackets, and torn jeans, a look of studied aggression on their faces, but nothing, really nothing to fear, and in a way mildly amusing: their black boots are still East Bloc soft, and these Bad Dudes walk out of their way at corners to cross at the zebra stripes. The coloring in the hair is a washed out shade of blue or red, nothing like the flames on a British punker’s shoulders, and ear rings arc limited, usually, to one per ear. One fellow has ripped out both cheeks of his pair of Levi’s, and flashes a lot of hairy ass at passers-by, but he’s the baddest of the bad. Alcohol is forbidden in Jarocin during the three days of festival, and inhale as deeply as I can, I sniff not a trace of Turkish Gold. Jarocin is Woodstock without dope, no threat of Altamont or Brixton. Even the foreigners from Holland, Germany, and England are well behaved.

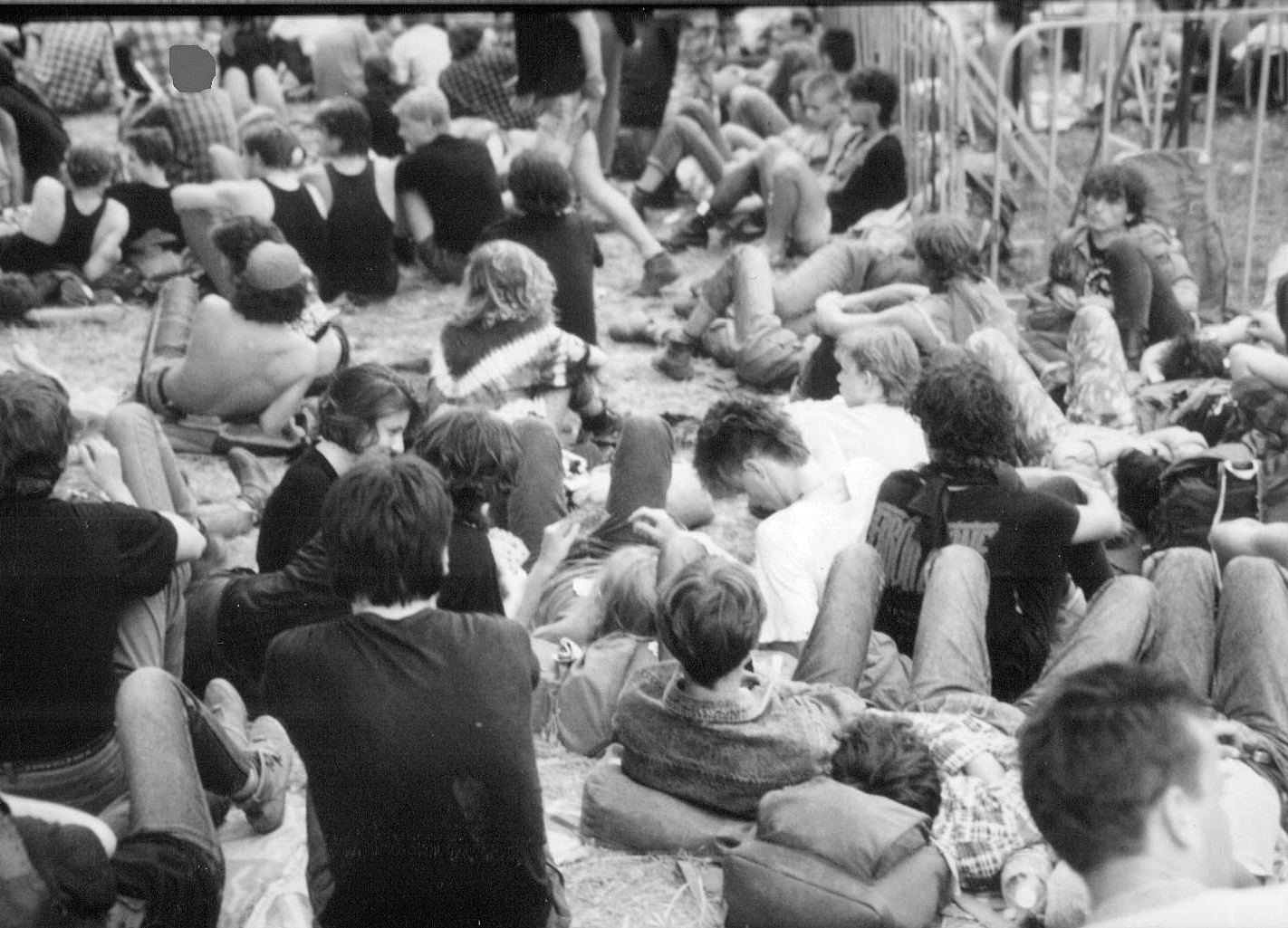

Or maybe they’re just a little fagged out. This festival has been going on for two days, building toward a big Saturday finish today: 24-hour music on the rock stage, and the folk stage and jam sessions in odd corners of town. Fans have been crashing in tents or on sleeping bags or just curled up on blankets for a couple of nights, sleeping as best they can, eating what provisions they have brought or care to purchase (very little price gouging, considering the opportunity: I would have thought citizens of Jarocin would squeeze this thing for more than they are apparently getting). Music freaks lie in heaps around the perimeter of the stadium, spaced-out black-and-blue sacks of unconsciousness, their brains trashed by overdoses of heavy metal. Walk carefully. Avoid the fence, which has functioned as a toilet for the past two days. Observe the fans, observe the middle-aged Western observers of the fans, observe the fans observe the middle-aged Westerners, observe the stage, the musicians.

The stage is simple by western standards: two banks of speakers stacked three high, blasting sound against your chest and ears as you walk by, the spotlight from the raised sound booth a hundred meters to the front, some overhead lighting, but none of the tangled, flashing erector set of tubes and lights and cables that accompanies most Western rock groups, gyrating and pulsating to their music, spinning, revolving, doing everything except count the gate and calculate gross receipts. For a backdrop, squares of white cloth stretched across wood frames,

painted in black with graffiti and silhouettes of the famous: Lech Wałęsa beside Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Elvis Presley, and Charlie Chaplin. “We want to go further and further… and to get a Mercedes.” In the gathering dusk, a half-naked lead singer impersonates early Mick Jagger as his drummer flails away behind him. If you can’t play well, play loud. Vibrations waft through numb ears into aggression-sated skulls which are mostly just resting, at the moment, before 8:00, when the heavies come on and live television coverage begins and this place really cranks up. What the hell—his kid can honestly say he played Jarocin, and nobody will ever ask whether he followed Pink Floyd or strummed an acoustic guitar in the men’s can. He’s even got a T-shirt to prove he was there.

We’ve played Jarocin too, Agnieszka and I, and we also have T-shirts to prove it. We’ve seen the heavy metal stage and all the punkers and their birds, perched like black vultures on the low railing beside the sidewalk entering and exiting the stage area. Noise rattles our ear drums. Threading our way through semi-conscious bodies, we reach the front gate just in time to see an ambulance, accompanied by several police, whisk some burned out hunk of a punker toward recovery in some atmosphere more serene than this stadium. Then we exit with the ambulance through a crowd of late-comers milling around the gate, perhaps hoping to buy a discounted ticket from somebody like ourselves, somebody leaving never to return, a little blue-and-black pass, “Festiwal Muzyki Rockowej/Agencja Rock Corporation,” which would admit them cheaply to that big finish. Maybe they intend to crash (seems unlikely: they’re pretty chilled out). Maybe they’re awaiting some moment late in the evening when the gate opens and music is on the house. Maybe they just want to hear what they can hear from the outside, which would be the Polish thing to do.

We’re also outside, headed for the folk stage, down streets lined with cars selling souvenir T-shirts, kiełbasa and ice cream, through a small park strewn with more black-and-blue bodies, past a battered Trabant with one of those plastic hands sticking out of the trunk, attached to a nearly invisible string with which the driver gives it a life-like twitch every thirty seconds or so. Past the old Protestant church where two fans keep candle-lit vigil in front of a makeshift shrine. To the folk stage (free at Jarocin ’91) where the amplification system is under control, where the music is, it seems to me, a little better and a little more variegated than what’s going on at the main stage.

Where we can sit on a wooden bench under the darkening sky and count the stars and listen to the tunes and talk quietly with each other.

(You know how these things work: the focus of attention is never where it’s at. What’s really happening goes down in a Street corner or on a side stage, enjoyed by only a few… who then spread the word, and next year what was out is in, but by then it’s not really in, because the focus of attention is usually never where it’s really at).

On stage when we arrive are a drummer, a bass, a guitar, and a clarinet. The clarinet works okay, although I’ve never before heard one in a folk group. Then a second Polish group, this one singing in English and in Polish, doing instrumentals with titles like “The District Attorney Defends Himself” and “The Stockholm Police Chase Each Other Through Sex Shops.” Far out! Then a Dutch folksinger, who opens with “the obligatory Dylan” (“The Wicked Messenger”) before moving to traditional Irish and British songs, including a mild political statement titled “Fuck the British Army.” A Polish folk group in full mountain costume: balalaika, drums, pipes, recorders, mandolins. One song from the nineteenth century is titled “It’s Good in America.” A Polish folk group from Warsaw, extremely professional, playing music from Ecuador. Even their leads are in Spanish: “uno, dos, tres, cuatros…” “This is the music of the future,” their leader preaches to the already converted: “natural music, nothing electric or synthetic about our instruments.” Video-cameras whirl around the group as it plays, and tape recorders: this bunch is obviously a favorite of organizers and promoters. I don’t understand why Poland should go to Ecuador to find the natural music of the future, but the musicians are professional in the extreme, including the single female (her red dress contrasts sharply with the black and grey parkas of the other musicians), whose main job seems to be to swing forward and back in time to the music’s syncopations. Ecstatic fans dance in the aisle.

More changes of sets and performers, each change necessitating careful rebalancing of microphones as performers of this natural music demand the most flattering electronic amplification possible. Members of different groups come together in ad hoc performances, singing Polish, Russian, Czech, and English. A duo from Britain offers debased Jethro Tull. The Jorgi Quartet appears, a very talented trio (despite the name) of professional musicians working out of Warsaw, their songs long and intricate with syncopations, counter-rhythms, and changes of key, their motifs mostly borrowed from Polish mountain music. Cello, bass, and metal and wood pipes. Guitar and bass are used as often as percussion instruments are as they are bowed, the very epitome of folk-art music, but quite popular here, and in Warsaw, and even in Łódź, where I twice heard them in the Jazz Club 77 on Piotrkowska Street.

Late in the night (or early in the morning) a group from Yugoslavia or Turkey (we are not sure) singing in some tongue neither of us can recognize, the lead singer given to shouting angrily into the microphone at the audience or the band, then returning the mike to its stand to stalk around the stage, even off the stage, like a tall, hunched-over bear, boring into his guitarist or the audience with coal-black eyes, long hair trailing behind him in the breeze, thence to return to his mike for more lyrics spitted angrily into the darkness.

By the time his group has finished, not a hundred fans remain at the folk stage. Not a vibration is heard from the heavy metal stage somewhere in the distance. Moonlight reflects from the polished surfaces of the cobblestones on market square as we return to the train station.

“What I would really like,” I confess to Agnieszka, “is one of those cloth banners that reads ‘Rock Jarocin 91.’ What a tremendous souvenir that would make.”

“Maybe if you ran really quickly,” she answers dubiously.

Then, quietly, almost to herself, “You Americans are very different from us Poles…”

Well shit—late as it is, cops abound, watchful as ever, and a few punksters straggling toward departure. I don’t need me or her or both of us to be packed off to jail, and what the hell, we have the bright peach T-shirts, and photographs as well, and tunes in the head and pictures in the mind, and just a little more insight into the soul of this remarkable people which so loves music of all varieties. It’s been a really good evening, one of the fine moments to keep locked away forever in my head. Why wreck it? Who needs a banner anyway?