No old leaded glass and no oil paintings in heavy gold frames. No shining mosaics, except one over the front entrance, quite plain and quite dirty. No elaborate bronze doors, like those on the cathedral in Poznań; no eighteenth century memorials on floors or walls, like those which grace churches in Gdańsk; no mediaeval or Renaissance tombs, like those in Kraków’s Wawel Cathedral. None of the magnificent contemporary stained glass that dazzles you in Wrocław. None of the elaborate baroque elegance of the Łowicz church, forty kilometers away, nor even the rich history of village churches at Rzgów (ten kilometers outside of Łódź), which dates to the late middle ages. No tour buses. No heat. No gimmicks. The Łódź Cathedral is simply, strictly business.

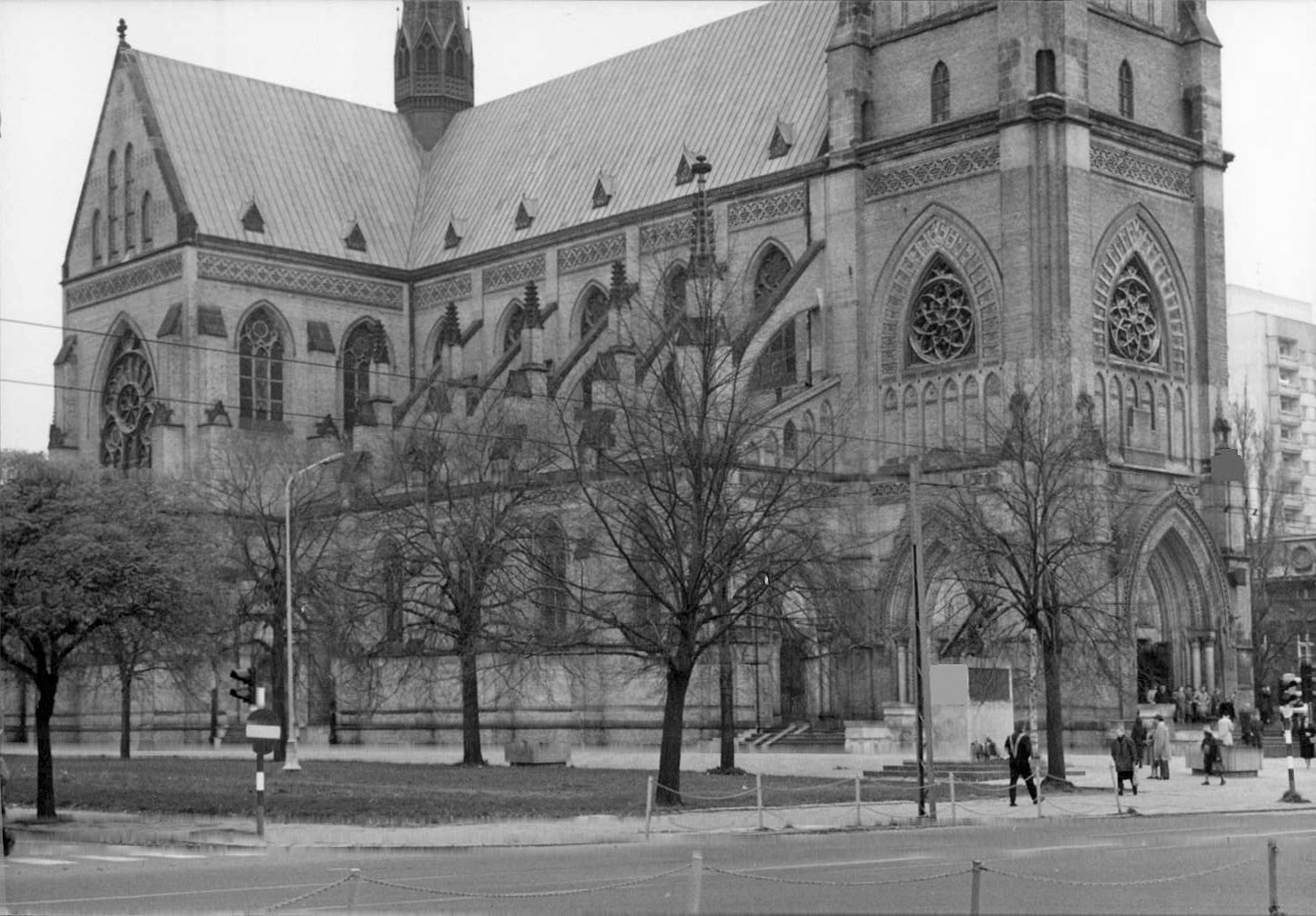

In fact, the Łódź Cathedral is shamed by the nicely restored and repainted building across the street, formerly part of the Scheibler-Grohman complex and more recently the gilded headquarters of the Party youth organization. At a moment when ecclesiastical buildings all over Poland are heavily into (expensive) repair, the Łódź Cathedral supports no scaffolding inside or out, despite serious structural cracks. It hasn’t been cleaned, or even tuck pointed, in years. The young trees in the surrounding park are neither sheltering nor elegant; the benches badly need paint. Plain cement steps lead to all entrances, absolutely without ornamentation. The statue of Christ carrying his cross with one arm and pointing with the other onward and upward, set on a raised pedestal to the south of the front entrance, lifts the spirits, especially when dusted lightly with snow. And the memorial to the unknown soldier, north of the front entrance, is noteworthy, especially on All Saints’ Day, when it’s littered with flowers and ablaze with votive candles. But for the most part, the Cathedral sits huge and solitary on the south end of Piotrkowska, open always for prayer and meditation and confession, in no sense alluring.

The Łódź Cathedral is yellow brick, erected between 1901 and 1912, with yellow brick buttresses and a single spire atop the front portal. The Cathedral is plain Gothic, a pleasing architecture, but a clean texture. If it does not lure, it pleases in its simplicity… especially when dusted by an early winter snowfall.

The interior is also pleasing in its simplicity. Relatively new, it has not been elaborated—or violated—with memorials in foreign styles, as have older Norman and Gothic churches around Europe, around Poland. Simple cross vaulting in the aisles and heavy stone (cement disguised as stone) piers in the nave support brick ribbed vaults above. On either side of the nave, not the tangle of privately endowed chapels common to older cathedrals, but a row of businesslike confessionals, with stations of the cross set between. The high altar is fine Polish neo-Gothic (1912) as are altars at either end of the transept: carved wood, polychrome, light gilding. In a small chapel behind the high altar, the obligatory reproduction of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa. A fine carving of St. Joseph on the canopy of the pulpit. Two wooden crucifixes flank the narthex door, the paint on Christ’s feet worn away by lips of the faithful. The neo-Gothic clerestory windows of the choir date to the early years of this century; windows along the nave are clearly 1950s, each illustrating a New Testament verse in glass of a pure, ungradiated, bright primary color. A white panel onto which slide images can be projected folds against the wall beside the high altar. The carpet is basic red, and the pews are a basic weathered pine.

Every visitor I have taken to Łódź Cathedral has been moved by its uncluttered architecture. In this regard it approaches better than more celebrated rivals the Gothic idea of space defined by a series of arches, with just a dusting of gold leaf and colored glass.

I spent limited time in the Cathedral myself: Easter, Christmas, a few private visits during the year. Easter was memorable mainly for the bad weather and the cold drafts, me without a cap covering my nearly bald head. What I got from Easter in Łódź was mainly a cold.

Christmas 1989 was a different story, an insight into Polish Catholicism. Michelle and I arrived half an hour early for midnight mass to find the Cathedral nearly deserted, except for a small group collecting contributions for Rumanian relief. This when Poland could barely feed itself, when the nation’s economic and political future was by no means secure. The emptiness of the Cathedral confused me: in the Lutheran tradition I knew as a boy, you get to midnight Christmas Eve service well before it begins, ahead of preliminaries like carol-singing and organ preludes, which extend, owing to the high holiness of the event, to thirty, forty-five minutes. Otherwise, you sit on folding chairs set up in the aisle invariably at the last minute. Or you stand in the doorway.

Here, however, Michelle and I sat in doubting solitude until ten minutes before the hour. Then people began arriving, pouring in, flooding the pews and the aisles of the nave and the transepts and everywhere, half the city of Łódź, chatting, chatting, chatting. Suddenly this

Christmas Eve was standing room only. The procession began not with tremendous organ fanfare, but with the ringing of a soprano bell and the clattering of clerical shoes on cold Cathedral pavement. Most parishioners gave it no notice.

Still people streamed in, most of them dressed to the nines, all quite awake including the kids, having a ball, seeing and being seen, almost nobody paying the slightest attention to the mass, perhaps because from where they sat they couldn’t see anything. I had a fine view of St. Joseph, but not of the altar, and the bishop delivered his sermon not from the pulpit, but from the transept. Even during his sermon, children and adults tromped up and down the central aisle, and crowds milled around both sides of the nave. Throughout the service a priest heard confessions in one of the rear confessionals, giving off a low murmur which nobody heard. Or minded. When a couple of drunks entered midway through the service and started a bit of a ruckus, the priest suspended his business, left his confessional, and ordered them out of the Cathedral in a voice none too sotto voce. Christmas mass proceeded oblivious to the drama.

When time came for communion, some partook and others did not: the whole operation was disorganized and confused. The music was remarkably bad—before, during, and after the mass, for liturgy and for hymns. Polish Christmas hymns are anemic, nineteenth century sentimental in contrast to the robust eighteenth century Adeste Fideles, sung in heaven by angelic choirs on this feast of Christmas Eve. Many worshipers left before mass ended, as many had arrived after it began, and the whole evening struck me as irreverently Polish loosey-goosey.

I felt the same about the wedding of one of our students, held again at the Cathedral, sandwiched between 4:00 and 5:00 mass, a hurried and apparently ill-rehearsed affair witnessed by friends of the bride, friends of the groom, and doddering, slightly confused parishioners left over from the 4:00 mass, or come early for the 5:00 service. Did anyone here know what was going on? Where I come from, you rehearse weddings, and Christmas Eve services, days in advance.

The subject of the Łódź Cathedral raises the issue of religion in Poland, how much Polish Catholicism is faith, how much is national consciousness, how much is political struggle. Early in my stay in Łódź, Agnieszka Salska gave me a postcard-sized cartoon of a priest and a bureaucrat standing on opposite sides of the street, staring in apparent nonchalance at each other, hands behind their backs, eyes empty. Behind one, a church topped with a cross; behind the other, an East Bloc bloc flying a red flag. The two figures just stand there, hands in pockets or behind the back, contemplating each other, so much left unsaid, so much said. That cartoon came to mean more to me as I watched the East Bloc crumble, watched the red flag of international communism become the red and white flag of Poland. Today the Catholic Church collects its dues, the price of its support in a bitter and protracted social and political struggle. Religious education is offered in every Polish public school. The Sejm debates a strong anti-abortion bill. During papal visits, condoms disappear from public shops. Even devout Catholics fear the Catholic hierarchy may become in the New Poland, as the Who once put it, “the new boss, same as the old boss. Don’t get fooled again.” The fact that John Paul II is Polish merely clouds with national pride to an issue of faith…or politics.

I can’t answer the question I just raised, and I doubt many poles could separate faith from nationalism from politics from superstition and habit. It’s easy to sentimentalize the Łódź Cathedral, or even the various Solidarity churches in this city, and it’s easy to intellectualize with analysis. This cathedral, that Christmas Eve mass was not sentimental nor intellectual. It was people doing what they do, a bedrock Given borne of habit or necessity, an action beyond volition, the great yellow brick foundation of the Polish soul.