The joke goes something like this: “What’s the best view in the whole city of Warsaw?”

“I don’t know; what’s the best view in all Warsaw?”

“The view from on top of the Palace of Culture.”

“Why’s that?”

“Because from there you can’t see the Palace of Culture.”

Yuck, yuck, yuck.

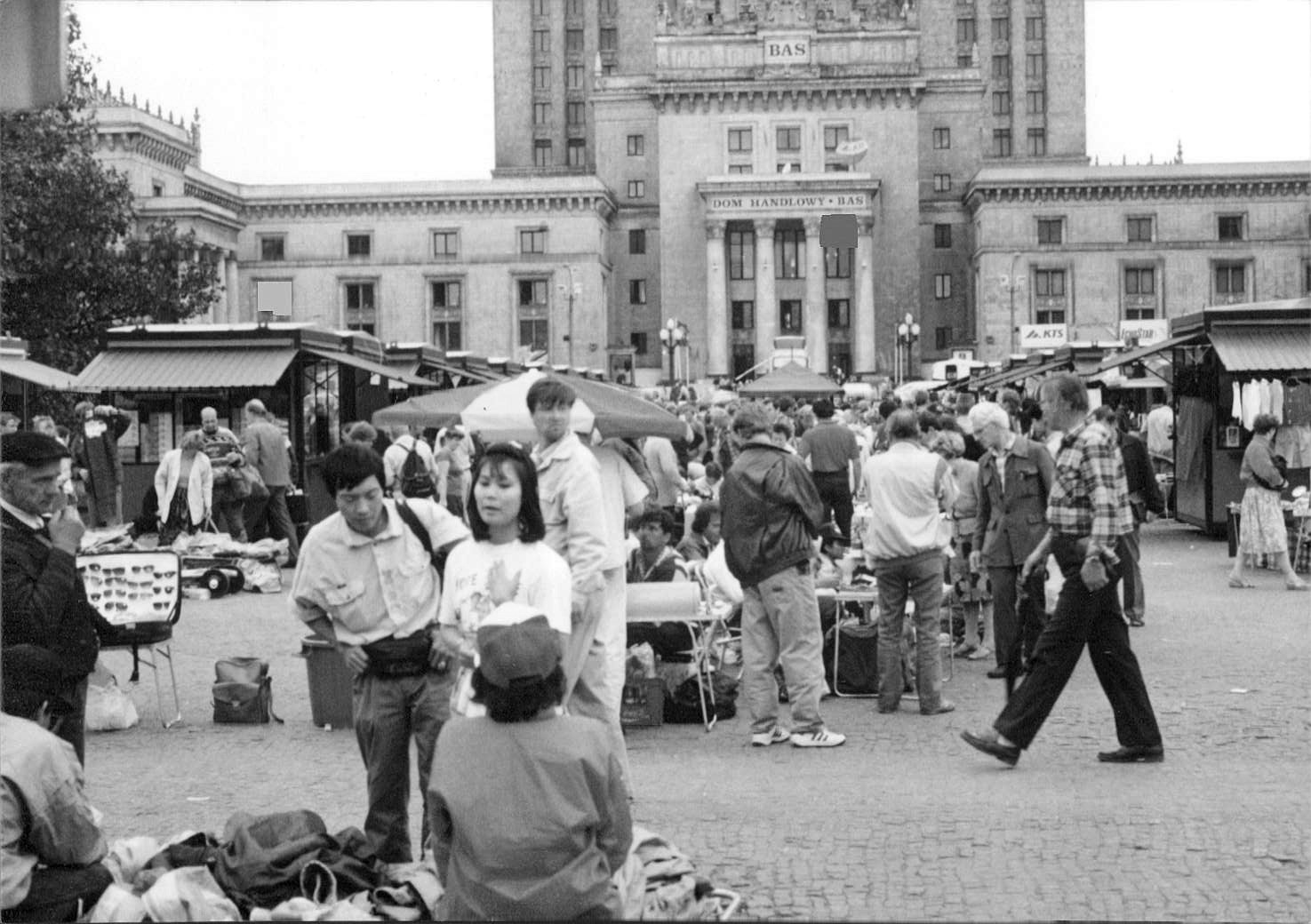

Joke’s on Warsaw. Humbled as it must feel these days, with a yuppie-puppie shopping mall inside and armies of Polish and Soviet capitalist wannabes in the parking lot, peddling their wares out of suitcases and boxes and the trunks of Ladas and Fiats, this mountainous stone memorial to Soviet-Polish communist friendship is probably the least pretentious thing in the city. True it does not fit into the Warszawian architectural style, but also true that the dominant Warszawian architectural style, despite a restored church here, a rebuilt Old Town there, is East Bloc drab. Boring, boring, boring. And pretentious, pretentious, pretentious.

Besides, how are you going to appreciate Old Town when you’re always looking over your shoulder toward the car, afraid that somebody is swiping the radio or the tires (not without cause do German auto insurance companies decline coverage on trips east of Oder), and you got one hand in your pocket holding onto your billfold, which you better hang onto because you’ll need it to pay for your $150-a-night room at the Marriott or Victoria or Holiday Inn, which is where you better stay while in this town, or you’ll wake up in the morning with the billfold and most of your luggage AWOL. And you are talking out of the side of your mouth trying to fend off the kids selling postcards, and the other hand is heavy with a bag full of Gorby dolls and Polish wood carvings, for which you know you paid three times the street price in Łódź or Zakopane, but these things are hard to find in Łódź and Zakopane, because they bring triple price here, and what the hell is a Gorby doll doing in Poland anyway?

The guidebooks bring you to Warsaw as one of Poland’s two or three major attractions: restored Old Town, the capitol buildings, the King Sigismund Column, the Adam Mickiewicz Monument, the St. John’s Cathedral, the opera, museums, gift shops, restaurants, Ghetto Monument, other churches, art Museums, University, Polytechnic, parks, embassies, riverfront… not to mention the country’s major international airport. But people, can we talk here a minute? Old Warsaw disappeared in 1939, the people, the life, the joy in life. The buildings disappeared in 1944, when Adolf Hitler sent a telegram and the Warsaw skyline was leveled to a pencil line. You can see the film and the photographs on display in the Historical Museum. As for the city rebuilt, let me refer you to the appropriate chapter of Jack Higgins’ remarkable anti-tourist book Season in Hell.

Warsaw is the New York City of Poland: overpriced, arrogant, dirty, dangerous, noisy, overcrowded, living off its past, basically unlovely for all the parks, memorials, and monuments. The odds on your pocket being picked while you photograph the Chopin statue in Łazienkowski Park are probably about one in ten. The odds on your parked car being vandalized are about one in fifteen. The odds on a private home inhabited by a known American being burgled during any given 12-month period are better than fifty-fifty. Fulbright lecturer Tom Samet was robbed in Warszawa Centralna not just once, not just twice, but three times. The third time his attackers used mace. Killing time one night in Centralna, Michelle and I witnessed, in the space of ninety minutes, one robbery, two muggings, and a drunken brawl in which one man’s head was smashed against the glass edge of the snack counter. When a middle-aged man started dragging his protesting wife up the stairs feet first, we decided to leave early for the airport and hang out there. The cab driver wanted $15 for what should have been a $2 fare; I found a night bus for 40 cents. One published story about cab drivers in this city is that at the very moment they’re gouging tourists on fares, they are radioing ahead in Polish, alerting accomplices at the tourist’s destination who will further abuse the visitor.

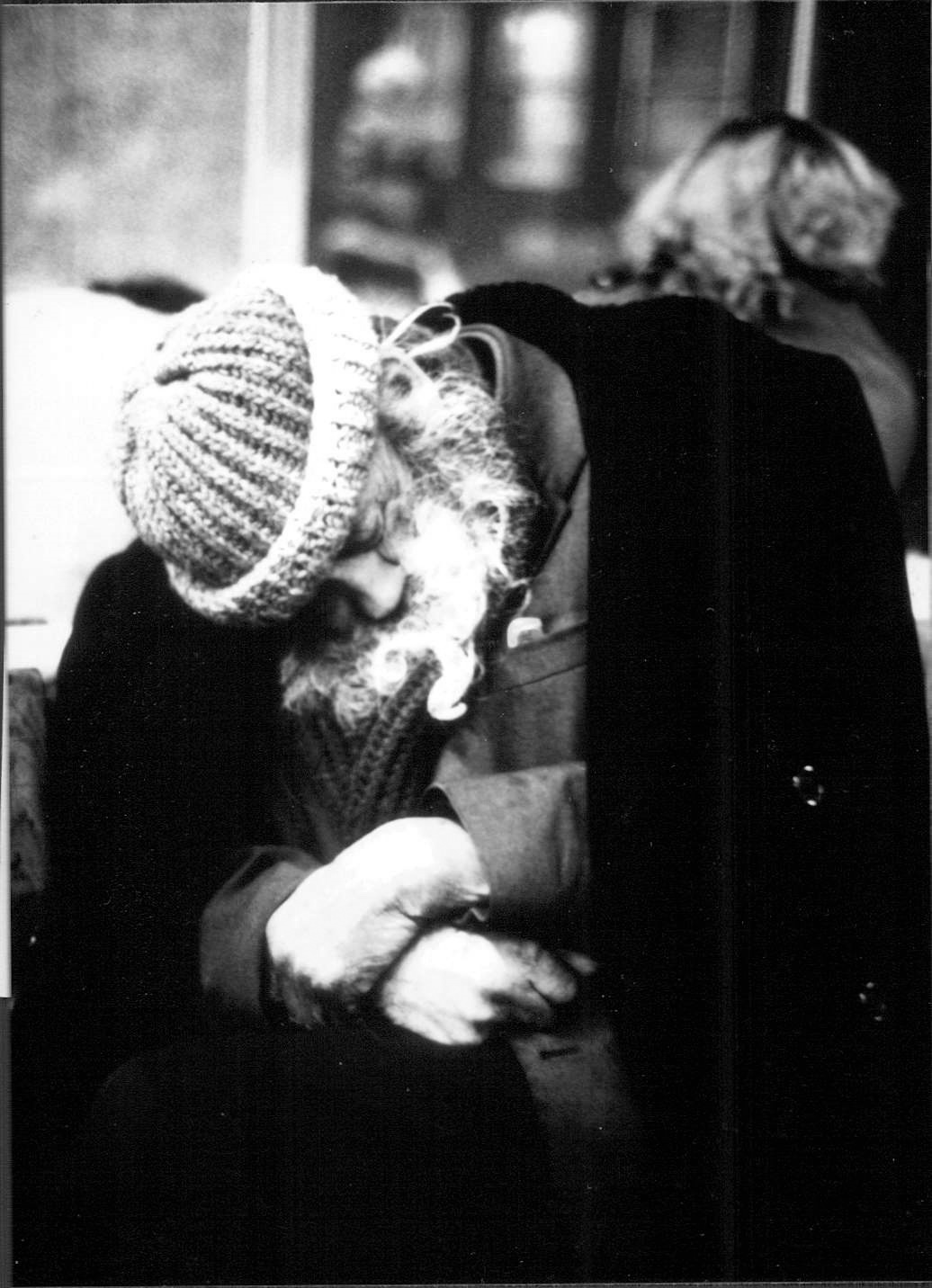

And trust me, the beggars moaning at you from every street corner are not all Rumanians. Nor are the panhandlers with their death’s-door faces, moth-eaten sweaters, and hand-written signs: “Please help me; I have AIDS.”

True, Warsaw has a river front, but this river is the Wisła, Queen of Sewers, its water unfit for use as the city’s water supply. True, Warsaw is the capitol of Poland, but it hasn’t always been the capitol: the old capitol, the city with all the fine old buildings, is Kraków, 250 kilometers south: same river, a different story entirely.

True, Warsaw offers better shopping than most other Polish cities, but today that difference is almost negligible, except in the area of prices, and for clothing Poles still shop Łódź. Warsaw has a McDonald’s, but so does every American town over 10,000 inhabitants. Warsaw has a sushi bar… but sushi is for yuppies. True, the Russian market sprawled around the Palace of Culture is the largest in Poland… but you get better goods, cheaper, in Białystok, on the eastern border. Warsaw’s Bong Sen Restaurant has better food than the Golden Duck in Łódź… but not much better, and the Bong Sen will cost you twice as much. Yes, the opera here is bigger and better than the opera in Łódź, but if it’s big opera you want, go the whole ten yards, go to Berlin. Besides, the new director of the Warsaw Opera is, you guessed it, the former director of the Łódź Opera. What’s happening at the Warsaw Opera today happened in Łódź two years ago. Last time I poked my head into an art museum in this city, the special exhibit was a collection of modern art on loan from, right again, the museum in Łódź. (By the time you read this, all those paintings will be back home again in Łódź).

And while the Marriott Hotel is one striking edifice, with brass-plated restaurants and chrome-plated shops, it’s just a typical American Marriott. What makes it stand out in this city is the contrast it offers to Warsaw drab.

Like New York, Warsaw is full of people who are irritatingly full of themselves, and for no compelling reason. Like New Yorkers, Warszawians go to work late, leave for home early, charge you double for making you wait. Like New Yorkers, Warszawians have been brutalized senseless by their environment, and they take their troubles out on you. In effect, the rest of the country is made to compensate inhabitants of this town for their misfortune in having to live here… although part of the compensation is that they get to remind you repeatedly of how swell they are. After a few years, even resident westerners catch the Warsaw Virus, becoming more native than the natives. Worst of the lot seem to be Americans who marry into the city, take jobs peripheral to the American Embassy, set up offices more or less in proximity to the Embassy, which they decorate with proper yuppie furniture in all the proper yuppie colors, install complex security systems and secretarial barriers to keep visitors away, post restricted working hours on their office doors to further discourage people from knocking, and set about flaunting their Polish-American eminence at U.S. government-funding receptions at the Marriott.

Fortunately, most Warszawians—like most New Yorkers—do not often venture into the hinterlands, so they will leave you alone unless you pester them. Unfortunately, there is too much power concentrated in this city for most Poles—and most Americans—to ignore it entirely. Besides, trains from Berlin arrive here, and airplanes from overseas. So probably you’re gonna see Warsaw, and you’re gonna stay at the Marriott or the Victoria, the Forum or the Grand. And you’re gonna get ripped, for at least one night. But the next morning, do yourself a favor: take your morning tea and cake at the Victoria, visit the Stare Miasto shop that sells those exquisite greeting cards decorated with dried wild flowers, visit the Russian market, and check out the open-air railroad museum just south from Warszawa Centralna, with armored railroad cars and old wooden boxcars and steam engines of all descriptions.

Then return to the Centralna, catch the next train out of town, and see Poland.