Understand from the beginning that Łódź is not exactly the Star of Africa in the royal sceptre of Poland. Arthur Fromer’s Eastern Europe on $25 a Day claims that Łódź “is considered Poland’s ugliest city, even by the Poles,” and mentions it only for the sake of readers traveling between Warsaw and Wrocław who need a place to stay. Or perhaps, the guidebook concedes, someone keen on architectural history might want to see what an ugly industrial city of the late nineteenth century looked like, with ugly workers’ apartments, and ugly textile factories, and ugly palaces of newly rich robber-barons. Such a person might come to Łódź to look at nineteenth century ugly. Otherwise, forget it! No classy restaurants, no elegant hotels, no Baltic beaches or wood-covered mountains, no restored marketplaces, not much shopping for anything that would interest most tourists. Nothing by way of high culture or art, no old cathedrals, no nothing.

Well, no… there is good opera and excellent ballet: the Łódź ballet production of Zorba the Greek (an inspired selection for spring 1990 with its conflict between individual and collective wills, between local and international sensibilities) toured Europe, winding up in Athens, summer of 1991. Those restored owners’ mansions are pretty snazzy, and old Piotrkowska Street has a neglected glory all its own. Moniuszki, once a private thoroughfare and not yet entirely gone, has appeared in nearly every Polish film set in the 1990-1930 period, many of them filmed at the internationally famous Łódź Film School (“HollyŁódź” read the graffiti). The Łódź branch of the National Art Museum houses the Polish modern collection, which is well worth seeing.

Still, Fromer gives an honest description of Łódź, 1989. This place is never going to compete with Kraków and Gdańsk, and its citizens admit the obvious. “It’s lovely here in the spring,” they tell you by way of excuses, as if every place, every person were not lovely in the spring. Unless compelled to stop for business or sleep or dinner, most people just keep on driving through Łódź, toward Warsaw, Częstochowa, Kraków, or Gdańsk.

On the other hand, except for the obvious differences between city and country, Łódź is a lot like the land I left in western Minnesota: a nondescript landscape through which one passes on the road between the lovely lake cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul and the scenic beauty of the Black Hills.

Łódź is not too different from most places on this planet: some theaters and movie houses, and some hidden surprises awaiting those who go looking but not much shaking, really. Just a scene through the car window on the drive of life.

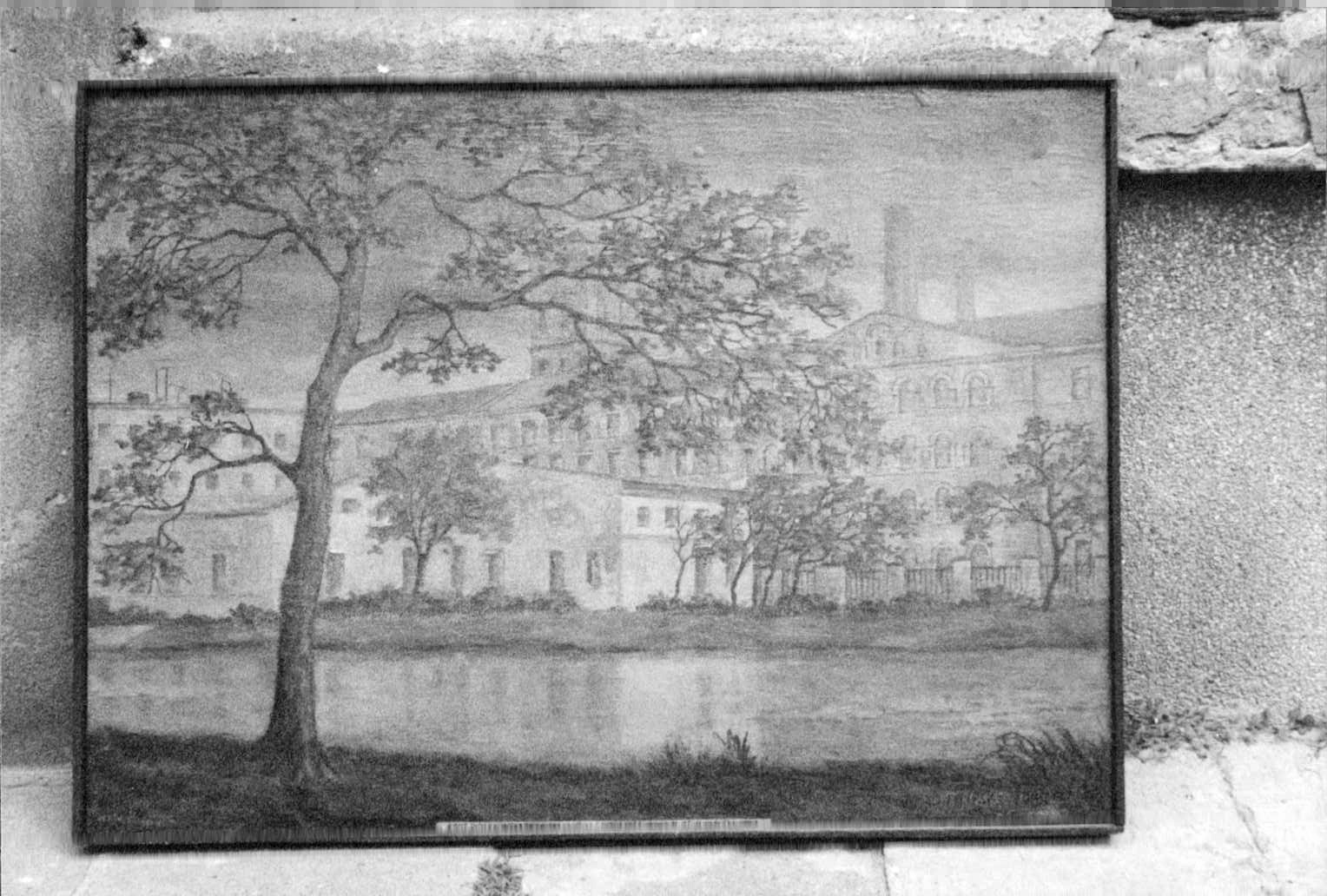

So I was surprised in finding a painting I very much liked at the Światowit Hotel gallery to discover that the subject was a Łódź street scene and the painter a Łódź artist. The scene was one of those old nineteenth century textile mills—“The White Factory,” as it is called, once part of the Geyer works on southern Piotrkowska—reflected romantically in the waters of its own mill pond, across from what was once the private park of its owner. The painter had caught the factory in deep shades of blue and gray, at the end of one of those overcast winter afternoons, with the low, polluted sky so characteristic of this city. It was a scene with which I could identify after only a month in town, something warm and comfortable despite, or perhaps because of, the somber sky and dark colors. The painting was priced at 180,000 złotych, and I almost bought it immediately. For $17, how could I go wrong? Only problems of transportation to the U.S. and wall space back home kept my hand in my pocket.

Something, however, compelled me to seek out the artist, to see other work, to be sure all of my $17 (the average Pole’s monthly income in fall 1989) went directly to the artist. I looked up the name Jan Filipski in the Łódź phone directory, and sure enough, there it was. A Polish intermediary arranged a meeting when we could look at pictures and talk art.

Filipski, I discovered, is 82 years old. Like many of the Old Ones of Łódź, he grew up in Warsaw, came to this city shortly after World War II when Warsaw lay rubblized and Łódź—protected during the war because of its historically German affiliation, and nearly emptied after the war because of both Jewish and German populations—had surplus housing. He has lived in Łódź ever since, first in old Bałuty, more recently in one of the tall, anonymous, gray apartment buildings on the city periphery. His flat is comfortable but not remarkable, decorated with a few of his own watercolors and assorted other unmemorable artifacts and reproductions.

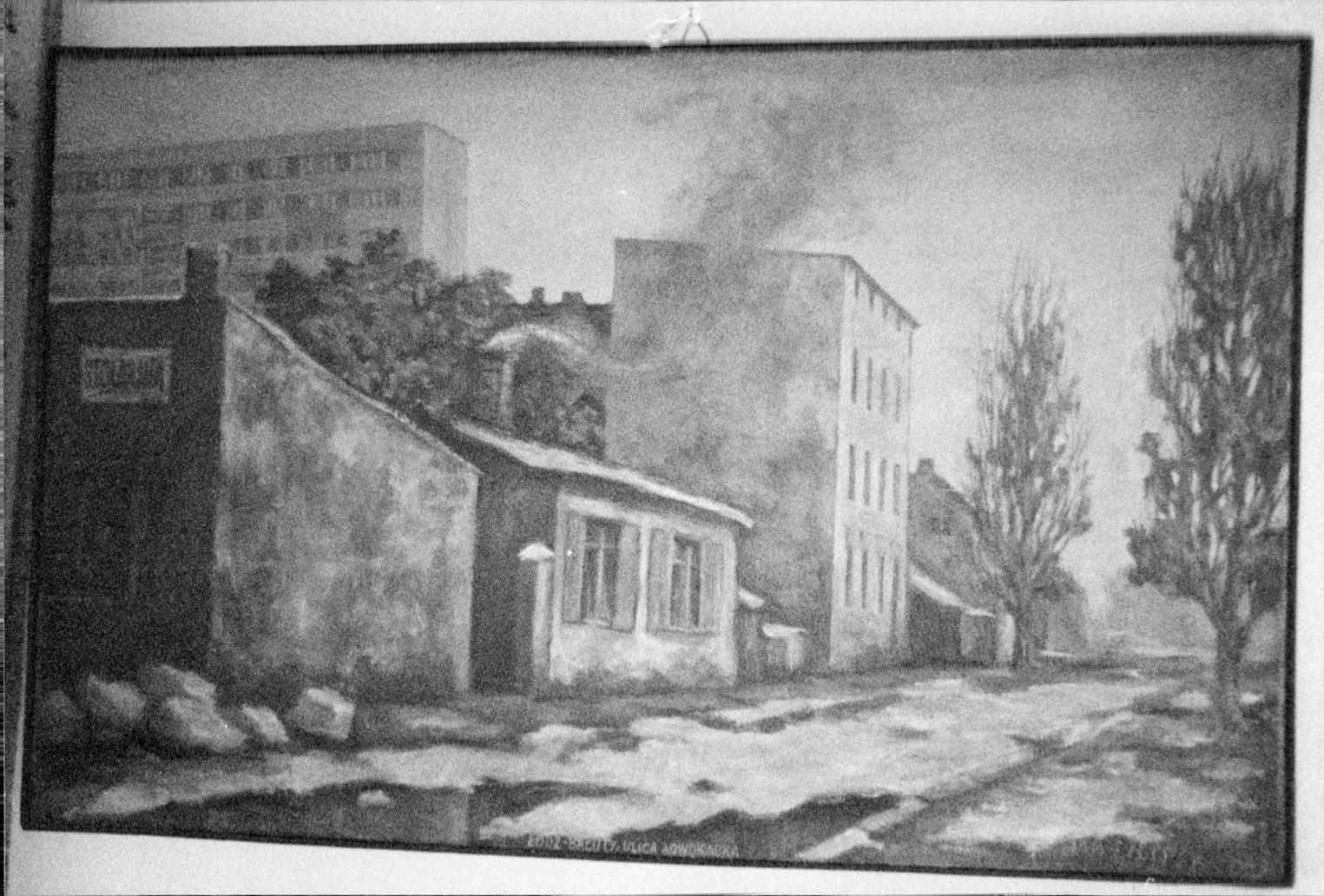

Filipski’s studio is a small room in the basement of a building around the corner, one room in the depths of an underground labyrinth vaguely resembling the cellar of the barracks at Auschwitz. He, Michelle, I, and our Polish colleague feel our way along brick walls toward a light switch, and then Pan Filipski opens the padlock on his studio door. A single bulb illuminates the windowless cell, filled to overflowing with the artist’s bicycle, very few painting supplies, and many carefully wrapped packages of his work. On shelves to the left of the door are stacked a dozen oil paintings similar to the one in the gallery: old Łódź factories and residences, street scenes from Bałuty, some fall, some dead of winter, all with those heavy Łódź skies, all the buildings in the same state of semi-disrepair, all with the same peculiar warmth.

The chilly room, more a hermit’s cell than a painter’s studio barely contains all four of us, and we must shuffle to rearrange ourselves as Filipski moves from package to pile to heap. This room, it occurs to me—this small, dank, subterranean cell—contains what remains of his life’s work: sixty years of drawings, paintings, sketchbooks, pictures.

“I have painted many things in many styles in my life,” the artist tells us. Untying the brown string on a package wrapped in cheap East Block paper, he shows us cubist work in the style of Picasso. He shows us etchings in the manner of Braque. There are wood block prints and steel engravings, a lovely series of silhouettes of Polish workers which I think I saw exhibited at another gallery in Łódź. He shows us series of rural landscapes, woods and parks, colors electric as those of Kandinski, ephemeral scenes along the lines of Turner. He shows us a slide of one painting, saying, “I cannot believe now that I could once paint this well.” Nothing he shows me resembles even remotely the heavy Stalinist sculptures and reliefs I see elsewhere in this city, the socialist realism I associate with East Bloc. No wonder Filipski never made it as a major artist. It’s a wonder he survived at all.

I ask about the factories and street scenes.

“This exhibit I put together in 1980,” he says, “although I had painted such scenes earlier and I continued to paint them after 1980. For the exhibit, I wrote this explanation, which I then painted on canvas.” Our intermediary translates:

To preserve in our memories the Bałuty that is now vanishing—this was the desire behind my decision to immortalize in my oil paintings and graphics these doomed buildings. There will come a day when we will look upon such houses as relics of the past, dear to our hearts, dear to the hearts of the people who spent their youth, and sometimes their whole lives in them: their final steps under motherly eyes; first loves; first hopes and disappointments; the morning and evening call of the factory siren rousing them from their slumber. The proletarian neighborhood of Łódź, soon to be gone forever, must be saved from oblivion! These are not the opulent secession-era mansions of Piotrkowska street, but single-story buildings with low hanging eaves, wooden fences darkened with age that enclose tiny gardens and yards teeming with all manner of birds, pigeons circling in the changing sky. This may be why my paintings are gray, melancholy and full of sorrow, sometimes brightened by a sprinkling of white or pale snow.Jan Filipski 1980

The paintings are scraped and battered: Filipski handles them with a carelessness an artist himself could allow only himself. Paint has flaked off one street scene, although generally the scratches and scrapes only enhance his subject, add more warmth to the art. “A bit of East Bloc realism,” I think to myself, “heavily flavored with Polish Romanticism.” In almost every scene a 1950s high-rise looms ominously behind the peasant homes, or factories, or older wood dwellings in the foreground. Some scenes I have already seen in pencil drawings and etchings, done either as studies for or revisions of the oil painting. In at least one scene, a high-rise visible in the drawing has disappeared from the painting. When I mention the fact, Filipski responds yes, for sure, it is gone. The new building was “not lovely,” not an attractive addition to the scene. Looking carefully at the painting, I see it has been painted out. “Not an attractive building at all,” he reassures us.

Is this an artistic statement or a political statement, or both at the same time? One must admire an artist who could accomplish so much within the confines of geography and politics which have circumscribed most of Jan Filipski’s years. How to work with some censor looking always over one’s shoulder? How to sustain one’s self with such small recognition? How to work in this damp, subterranean cell, the only light a naked bulb dangling from an electrical cord in the middle of the room? How many other artists, in Łódź, in Poland, have spent similarly hidden lives?

Thinking about it, I realize that similar confines circumscribe all of us, writers and painters, poets and peasants. All of us live in some Łódź or another… but only in falling into what Robert Bly once called “our crummy little place” do we discover at last our own true materials, no matter what we set out to accomplish. Filipski has done for Łódź what poet Dave Etter did for Illinois, Larry McMurtry for Texas, Garrison Keillor for Minnesota, Ken Kesey for the Pacific Northwest, and Carolyn Chute for Maine. What all artists worth their salt must do for a community, what any community should demand of its artists: “Give us our place.” The artist’s first duty is to his own place. Wrote Etter, “The lifeblood of any nation’s literature has always come from writers who write primarily about one region, one state, one slice of familiar real estate, and I hope and trust that this will always be true.” The same can be said of painters.

Part of me believes that these paintings are a treasure which should never be allowed to leave Łódź: unlike words, oil paintings cannot be endlessly duplicated and reduplicated. But another part of me wants desperately to take home a little piece of this place, even though I will spend only a couple of years among these buildings. So we settle on a price for one of Michelle’s favorites, $60 in hard currency. The artist is reluctant to part with his five year old child, but he wraps it carefully in brown paper and coarse string, forming a handle with which I can carry it. Then he turns out the light in his tiny studio-bicycle shed and sees us all to the tram. I promise him that I will write something, and I promise myself that I will hustle right over to the Światowit gallery and buy that other painting as well.

Which I do. But when I get there the next morning, its price has inflated overnight. To just around $60.

This story has a number of postscripts, including the reaction of Gabriele mentioned earlier. The first came a week after my visit, when I was recounting the story at the English Institute by way of commenting on inflation in Poland. “From 180,000 to 650,000 złotych, overnight,” I said, shaking my head in disbelief.

My students look at each other and one of them laughs. “You yourself caused the price to increase,” Agnieszka Tynecka points out. “A week ago this painter was nobody; today he is an internationally famous artist. Some American is interested in his work. Bought two and going to write an article about him. And in Łódź, of all places! Think of that!”

“So,” I think to myself: “by being true to his own place, the artist reaches out to people and places all over the world. That is the way it is supposed to work.”

A second postscript came in spring 1990 after the Marshall Independent had published my essay on Filipski, largely as it appears here. The paper sent me a tearsheet, of course, which I photocopied and mailed to the artist, as a redemption of my pledge to write a piece. I heard nothing from Filipski, but when I finally gathered money and courage to buy one more Filipski painting (all right, I bought two more, the only two remaining Filipski paintings for sale in the city), the sales clerk at the gallery asked me in perfect English, “Do you know this painter?”

“Yes, I do,” I said. “I mean, I have bought some of his other work, and I visited him once. He lives in Łódź. He is quite old.”

“You wrote an article about him,” she tells me. “Your name is David Pichaske…”

The final postscript, I suppose, came in November of 1991, on my return visit to a Łódź half way on its way to the West. “The City Museum in Poznański’s old palace has just opened a new section,” Agnieszka Salska told me and my Fulbright successor, Kate Begnal. “Would you be interested in having a look?”

So look we did (at a dramatically inflated entrance fee), upstairs at the Rubinstein rooms and downstairs at other exhibits, and what do you think we should find on exhibit in the Łódź City Museum? A whole room full of Filipski oil paintings just like the six on my wall in Minnesota, including several the painter showed me that first visit, and the painted inscription done for the 1980 exhibit.