The big story in Poland 1989-91 was economic, and that story was bipartite. Inflation, as everyone remembers, was horrendous, despite self-serving claims by the new government and American economic advisor Geoffrey Sachs that economic “shock treatment” stopped inflation dead in its tracks during the first quarter of 1990. No such thing: all prices rose continuously through 1990, except the price of the U.S. dollar, which, through some monetary hocus pocus, held steady at about 9,500 złotych throughout the year, down from 11,000 or 12,000 on the street in August of 1989. Tram and bus tickets, to take a more or less random example, shot from 30 złotych in August 1989, to 60 in September, to 120 in early 1990, then to 360, then to 400 by August of that same year, to 700 in December, and to 1200 by early 1991. Whenever people ask about inflation, I pull out my Łódź bus-and-tram pass, a small document with photograph and number, validated by affixing a small stamp purchased each month at the Rectorat. The price of the stamp for 11/89, I show them, was 7,000 złotych. The stamp for 1/90 bears a price of 14,000. The stamp for 3/90, 24,000; that for 5/90, 45,000; that for 1/91, 70,000. The stamp for 4/91 cost 100,000 Polish złotych, substantially more than Tom Bednarowicz’s parents paid for their summer cottage slightly more than a decade ago.

“How did Poles cope with that kind of inflation?” people ask me. “The way you might expect,” I tell them. They printed more money, introducing first a 50,000-złotych note, then a 100,000 note, then a 500,000 note, and finally, yes, a 1,000,000-złotych note. When we collected our monthly pay at the University bursar’s office, the serial numbers of our crisp new bills were always in sequence. Most Polish salaries also inflated during this period, from an average of 200,000 per month in fall 1989 to an average around 2,000,000 per month in spring 1991. People who lost their jobs suffered economically. Everyone suffered vertigo.

The other side of the Polish economic story, the up side of inflation (coupled with the stable foreign exchange), was increased supplies of every conceivable consumer product and service, to the point that in summer of 1991, you could buy anything you wanted, in any quantity you wanted, on the streets of Poland. Westerners will find no surprise here: increased prices mean increased goods. Remember the gasoline shortages of the 1970s, and the gasoline glut that followed, once prices ballooned from 29 cents a gallon to over a dollar? We have been there before, you and I.

Poles, however, had lived their lives, and their parents’ lives as well, in a world of controlled production and more or less controlled distribution. An aircraft-carried sized building in Warsaw decided what would be produced, and where it would be shipped. “Look how huge,” a taxi driver exclaimed in English, pointing to the great block of cement and glass; “and look what all their decisions brought us!” Goods did not appear, and what was not available, people could not buy. Or goods did appear, and if what appeared was not what they wanted, they bought anyway, because there was nothing else on which to spend their money. I remember heavy-duty chain hoists, the sort used to derrick automobile engines out of cars, appearing one week in a shop on Piotrkowska in the fall of 1989. They were cheap, maybe fifteen dollars. The shop was full of them, and people were buying them. In a month, the supply was exhausted, and I doubt they’ve been available since.

Precisely because goods might not reappear for quite some while, people usually bought two or three—even refrigerators and television sets. Or they converted their złotych into dollars, which they stuffed in a mattress. Food especially was stockpiled. When I complained early on about shops running short of rice, one colleague said, only half-jokingly, “Any Pole would have a six-months’ supply.”

In fall of 1989, people were mostly not buying, although the situation had improved from the famous “peas and vinegar” days when only those commodities could be found on most state store shelves, and Polish women spent their time in queues exchanging new recipes for preparing peas in vinegar. Sugar had been unavailable for months (although bakeries and restaurants were kept supplied, and the Pepsi Cola bottling plant), and colleagues left work without censure or pangs of conscience on the mere rumor of sugar in this store or that, to wait long hours in long lines in hopes of buying the two-bag limit. I once witnessed a near riot triggered by the mere mention of sugar: a stout middle-aged woman in a gray coat at the head of the line made the pro forma inquiry, rather too loudly, “Do you have any sugar?” She received the usual “no,” but the answer was too quiet to be heard. Then she bought two bags of something that looked a lot like sugar—probably flour, although a number of commodities were sold in those plain brown bags—and one woman well back in line got the notion that those were bags of sugar. “You’ve got sugar??!!” she shouted in great hope and enthusiasm, which brought everyone running, pushing, jostling, until the clerk climbed on the counter and barked impatiently, “No, I do not have sugar today!”

Customers pilfered sugar from restaurants, a few teaspoonfuls folded in a napkin and tucked in the pocket, until managers removed sugar cups from the tables. At the Embassy commissary, granulated sugar—trucked in from Berlin—disappeared upon arrival, as Americans bought for themselves and for Polish colleagues. Michelle and I contented ourselves with sugar cubes, counting ourselves lucky and pulverizing whatever we needed for baking.

Toilet paper was also a problem, and remained a problem long after the 1989 sugar beet crop had been harvested, refined, and distributed. You could not get TP anywhere, not even at the private markets. I once saw a fellow bring a pushcart of toilet paper out of a doorway on Piotrkowska; he wasn’t a hundred yards down the street before it was sold. In mid-December the University distributed rolls of toilet paper to all its faculty as a very welcomed Christmas present. This odd year-end bonus (and two 8-roll packages of paper brought from the States) saved us from having to follow the lead of other Poles and shred newspaper or magazines (but not the Sears catalog, a much-prized item in Poland). In better hotels, you could buy a few sheets from the WC attendant for 200 zł, but most of the time there, as on the trains and in underground conveniences, and even at the University, you found shredded dailies, if you found anything at all.

There were other shortages: clothing, food, toys. Everything except bread, milk, jam, and cheese. I remember long lines in the Central Department Store, waiting five minutes to get on the escalator to the second floor, then finding in the shoe department perhaps three pairs of shoes, in the toy department maybe a couple of heavy Russian bicycles. I remember once being absolutely unable to find pork anywhere in the city of Łódź, population 900,000. When we couldn’t find drinking glasses, a young medical student who took private English lessons from Michelle promised, “Don’t worry, my mother will get you some.” But Rafał’s mother couldn’t buy drinking glasses either, and after a three-week search donated six of the family’s own to redeem her son’s promise.

A rule obtained in those days, which foreigners learned quickly: if you see it, and you or a friend might need it, buy two. Much of every Pole’s cache came from the black market or the private market (which I saw only in vestigial operation), which is why people had warned us on entering Poland, “Don’t try to go it alone. You need a network of Polish connections—or a friend who has a network of connections.” Part of every Pole’s life’s work was the cultivation of such a network to supply coffee, sugar, car parts. (One student entertained Michelle and me in a house her father had built for absolutely nothing, trading with his network for all necessary materials, labor, permits, furnishings). The Fulbright Commission directed host institutions to provide visiting scholars with “shepherds,” who could provide networks into whom they could plug.

Networks are no longer necessary in Poland—not when it comes to buying sugar or toilet paper, and not even for tricky operations like obtaining official export documents for works of art, or buying special car insurance for trips to Austria or Germany. Nor is it necessary to spend hours in a queue, or to hire others (as did some of my American friends) to queue for you… or to hire others (as did some of my American friends) to queue for you… or to boast (as did other American colleagues), “I do not queue,” putting, always, a little spin on the not. The black market became the street market, and inflation brought an avalanche of consumer goods, even luxury items like olives, peanuts, diet cola, Polish ham, coffee, soy sauce, Heinz catsup. Foreigners who had not kept abreast of the emerging Poland could be embarrassed: one Austrian arrived in spring 1991 with a small suitcase full of coffee. He’d been told coffee would make handsome gifts for his hosts… and at one time it would have. Chocolate and coffee: two staple gifts in the East. But by spring 1991, chocolate and coffee were available everywhere west of the Soviet border. “I can’t give this to anyone,” he confided in me; “I would embarrass them and myself. Do you have any use for it?”

In spring 1990 prices rose so high, and stock piles of consumer goods were so great, and Poles were so suddenly cautious, that the unimaginable actually happened: supply exceeded demand. Discounts appeared, and sales on all sorts of items, up to fifty percent off, even on the pirated “designer” clothing with Gucci and Benetton embroidered across the front. “Okazja!!!” the handwritten signs announced. Sales! In Poland. Who would have thought it?

We were witnessing in Poland the construction of a private market out of elements of the old black market, the underground network of hidden suppliers and consumers, and what remained of the merchant class. That construction crossed a great distance in a very short time, bounding from one phase to the next in a matter of weeks or months. First the black market emerged from the closet as a public but carefully monitored hodgepodge of bazaars and street markets, some in traditional market areas (the market by Centrum, for example, and the market in Bałuty), some in non-traditional but strategic central Łódź locations (in front of the Opera, or in the Central Department Store parking lot), some in fields on the outskirts of town. In early 1990, private peddling exploded all over the streets—again with official sanction—before stabilizing later in the year into individually owned private shops, some along the city’s major boulevards, some hidden in back courtyards and secondary streets, some in rented kiosks: corrugated steel over two-by-four frames, or molded plastic, factory-produced, trucked in, and deposited at key intersections around Łódź. (This was about the same time that currency exchanges became legal, moving off the street corners and into private shops. One is no longer pestered in Poland by greasy thugs whispering “Change money? Change money?”) Inevitably some private shops failed; a few shops expanded into chains. Then wholesalers appeared (they sold both retail and wholesale): by fall, 1991, everyone with a free-standing house on the edge of Łódź seemed to operate a hurtownia of one sort or another.

Shopping in Poland was an exercise in hanging loose: just when you developed a feel for the system, it changed. You had no sooner structured your Saturdays to include a weekly visit to the Super Bazaar at Kaliska Station, then you realized there really wasn’t much shaking at Kaliska last week… or the week before that either, come to think of it. Where did everyone go? Or one day you hiked over to the Central Department Store parking lot, intent on buying maybe a kilo of pork from one of the truck-butchers, and the whole operation had disappeared—not a truck or table anywhere. Or suddenly shops were staying open evenings, or weekends, or even 24 hours a day—first just the Stanley shop on Piotrkowska, then many, if not most retail stores.

Or suddenly Kilińskiego Street had blossomed with all kinds of spiffy new shops, with colored awnings, plate glass windows, and a fresh coat of paint (not an entire building, mind you—just on street level, and only as far as the shop extended). Argentum, that new jeweler next to Hortex, was accepting Master Charge, Visa, and American Express (although it took nearly an hour to clear your card number with Warsaw). A new Julius Meinl shop—Austrian chain—had opened on Piotrkowska, up the street from the “House of Beer” and the shop that sells leaded glass lamps for $800. The news stand on Narutowicza had installed a 1-hour film processing machine (within a month, six other such machines appeared elsewhere in Łódź, including in the Polish craft shop, “Cepelia,” by the English Institute).

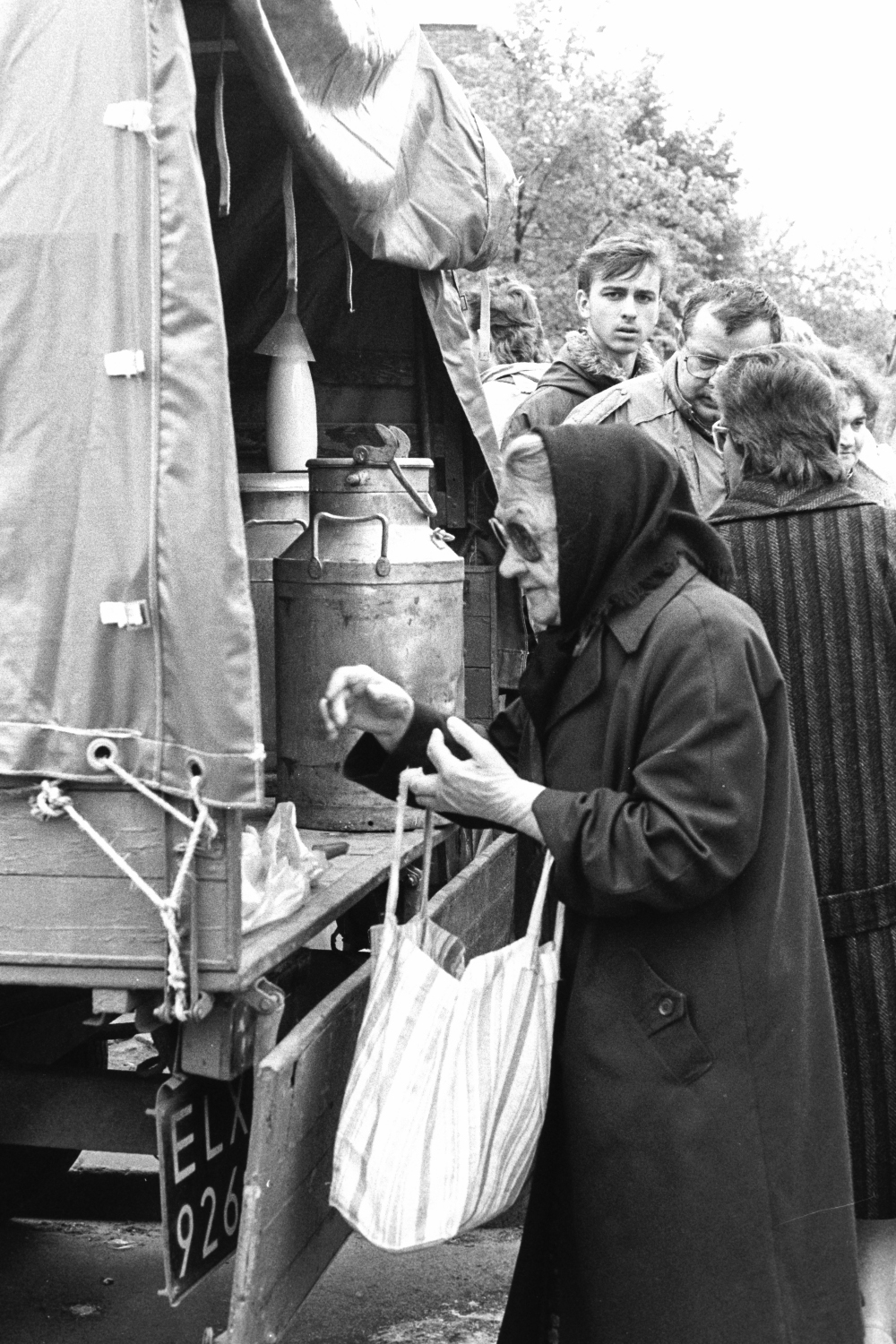

Street markets played an important role in the emerging free Polish economy, and even today Agnieszka and Grzegorz Siewko, who run a small dress-making business, sell more at a street market than in private shops, identical prices both locations. For at least a century there has been an active street market in Łódź, as in all major European cities, the vendors an odd mix of professional middlemen and farmer-producers. Prices have always been low, and commodities traditionally basic. In Love and Exile, Isaac Bashevis Singer remembered markets in Warsaw “where one could get black bread for half price. Peasant women brought cheese, mushrooms, groats, and onions from the country that I could buy for next to nothing.” Tuesday and Friday are traditional Polish market days, but in a city the size of Łódź activity continues every day, except for high holidays and Sunday. Some merchants set up inside wooden sheds about the size of a modest garden house, or in a booth inside the actual market building (new to Łódź in fall 1991; market halls were popular long before that in other cities like Wrocław and Gdańsk). Others spread their wares on wood or concrete tables provided by the city. Many bring a table or a folding cot. Some simply open their suitcases, or pile goods on newspaper spread on the street, on cardboard or cloth or just there in the mud or dust. Or they hold goods in their hands, dangle gold necklaces and bracelets from their fingers, wear fur or suede coats on their backs. The market is full of sheds, carts, cars, trucks, wooden crates, cots, planks, cardboard, tables, Poles, Ukrainians, gypsies, Russians, craftsmen, farmers, hucksters, hustlers. I have seen versions of the old shell game, complete with hired shills, and Boardwalk-style demonstrations of miracle kitchen gadgets guaranteed to slice, dice, cut, and curl a wide assortment of vegetables with no effort at all, money back if you are not completely satisfied.

You’re supposed to bargain, of course, but I rarely do. Prices seem surprisingly consistent, even on the flea market items, and they’re low enough for me. 50,000 for a grey Russian fur cap? I’ll take it! “You should have bargained with him,” Ewa Ziołańska tells me.

“50,000 is cheap. What would we have got it for do you think?”

“40,000 probably, maybe 35,000.”

“50,000; 40,000. What’s 10,000 złotych?”

“10,000 is half a pizza. Do it twice, and you’ve got a free lunch.”

In spring 1991, the market by Centrum (the intersection of Pabianicka, Piotrkowska, and Rzgowska) is the liveliest in Łódź, especially on a Saturday morning: mushrooms, cut flowers and bedding plants, baskets for shopping and laundry-sized hampers, fruit (bananas, peaches, rhubarb, kiwi, oranges, cherries, strawberries at 20 cents a pound, lemons, apples as always) and vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, onions, cauliflower, lettuce, radishes, cabbage, potatoes as ever). There are straw hats, River Cola and German chocolate bars, coffee, peanuts, Turkish sweat- and T-shirts with the usual English slogans (“American Superbowl, Beverly Hills,” “Navy Marine Seaporf,” “Space Age: 21st Century,” “West California State, Las Vegas, Nevada”), slippers and shoes, plastic shopping bags bearing the likeness of Michael Jackson or the Lucky Strike logo. There are vegetable peelers and kraut cutters, ladies’ undergarments, umbrellas, racks and racks of the old East Bloc clothing so out of fashion even Central won’t stock it. These beside pseudo-designer shirts bearing names like “Gucci” and “Chanel, Paris” and “Benetton.” Peddlers offer pirated video tapes including Dirty Dancing and Rambo, Madras shirts from India and dress shirts purportedly from France and Italy, Playboy magazine, gold jewelry, fur coats and animal furs ready to be made into fur coats, seeds, and bulbs sold bulk from cloth bags, flour and ground grains from larger plastic sacks, leather belts and watchbands, cosmetics, a Westa sewing machine and an “overedging sewing machine made in the People’s Republic of China,” a Soviet microscope for $35 and Soviet binoculars for the same price, Western telephones, Sharp and Goldstar VCRs, stamps and coins—including a Maria Theresa thaler and a 1922 U.S. silver dollar at $10—brooms with green leaves budding on the twigs, eggs, bolts of textile and bobbins of thread, vinyl floor covering, fresh fish and smoked eels, an unusual number of drafting sets and sets of drill bits, leather jackets without labels, live ducks and geese and bunnies. There are flea market items and military regalia, from Soviet army caps, belts, and medals to a Polish medal for service in World War II underground. Even Nazi medals. It’s not unusual here to see customers strip to their BVDs, even in winter, trying on jeans between the wooden sheds along “clothing alley.” Or in the spring to see peasants scoop great clouds of downy chicks or ducklings from one box to another, selling by the dozen, count ’em after they’ve been poured from seller’s box to customer’s.

This market has settled into zones, which are being made gradually more permanent by the construction of wooden or corrugated steel sheds and the raising of metal fences: food stuffs, electronic goods, fur and leather, cotton clothing, bikes, automobile parts, stamps and coins, watches, gold and jewelry, and meat (most butchers now being located inside the main market building). Furriers’ row is particularly fascinating: you can buy coats—suede and fur—or pelts of any animal from skunk to silver fox. I once watched a peddler and customer haggle over six or seven magnificent white mink pelts. After a brief but intense discussion both nodded, and the customer stuffed those lovely white furs into his plastic shopping bag as casually as I would eat a French fry.

Toward the rear of the market, in the area of permanent structures where the old East Bloc fashions are sold, are the shops of several shoemakers: men fashioning footwear from scratch, to customers’ specifications, tacking and sewing wooden heels, thick leather soles, and pieces of shoe leather cut from hides of various hues and textures. One man wanders through the crowd selling Lody Bambino—chocolate-covered ice cream on a stick—from a cardboard box. Girls in black and white dresses buy bright costume jewelry. The Old Ones hunch over their wares, selling, selling, selling. And always there are the young, aggressive male Polish traders, eyes sharp for a sale, dangling wares from their hands, giving a slight jiggle to catch your eye, as you would lightly jerk a Little Cleo after casting it in front of some large-mouth bass.

Today dirt is heavy on the sidewalks, dusted by buses and cars over the kiełbasa and other sausage, over the lungs, chickens, tongue, liver, bacon, and kidneys. Some meat is shaded by umbrellas, truck roofs, or other forms of covering, but most is not. One vendor swishes flies off his beef with the branch of a tree. Another butcher hacks away at the skull of a pig, splitting it in half for somebody who only wants a half a head of swine. At another stall, the skinned skull of a steer, picked nearly clean of flesh. Beneath another makeshift counter of crates and plank, a plastic basket full of plucked chicken heads.

The gold-sellers are out in force in one corner of the market, hands in the air, half a dozen rings on each finger, chains wrapped around their arms, broaches pinned to their blouses and jackets. The gold is a deep red color, either a copper alloy or very high karat, but the bands are thin, and what appears to be a large ring is surprisingly light. One expects deception, of course, even with jewelry smuggled out of gold-rich Russia, but not too much deception: a licensed jeweler has parked his camper nearby, and for 2,000 złotych he will test the ring you intend to buy. A scratch on a test plate, a drop of acid. Yes, this is genuine gold. How buyers can be sure this jeweler is not on the take, I can’t say, but they seem to believe. Poles are clever tricksters on one hand, naive children on the other—something that will make an interesting and fair fight once Poland confronts unprincipled capitalism face to face. Anyway, this jeweler has been here many months now, and, if he is indeed a scam, should have been detected long ago.

In front of Centrum stands the line of puppy merchants: boxes, suitcases, Big Shopper shopping bags wriggling with dog flesh, warm and soft-furred and puppy-breathed. Shepherds, Dalmatians, mutts aplenty struggle toward freedom, always to be pushed back into the bag. Usually a mother dog stands nearby, reassuring potential buyers with a nod of her head, “Yup, that’s my baby. She’s a Shepherd all right. Look just like me in a couple of years.” Ewa says they are all diseased and will not live six months, but one is cuter than the other, and I have learned to keep Michelle far away from the puppy-peddlers. She alternates between one plan to “buy a pedigree Newfoundland here cheap, and fly him home while still a puppy; he can sleep in a basket on our lap,” and another plan to buy every puppy in the place and give them away to good homes, thereby bringing joy to kids all over the city and saving the pups from certain drowning. “David,” she will tell me earnestly, “somebody has to save these puppies!”

Many peddlers are Russians, Ukrainians, Central Asians come to Łódź to sell clothing, tools, matrioshka dolls and designer “perestroika” watches, vodka and Soviet champaign (now $5 a bottle), caviar ($6 a tin), and children’s toys. Their “tour” buses are usually parked somewhere in the field along Rzgowska. But it is the Old Ones who most interest me: the old woman seated on an overturned plastic bucket, hands folded on her lap, on the ground in front of her five live rabbits in a cage, two dead chickens, a stack of eggs, a bag of salad lettuce, and a few bunches of radishes. The man selling the kraut cutter he obviously built himself. The weathered peasant standing patiently in front of an old balance scale, all he had left to peddle (I bought it for $10, and he packed it in a cloth bag, handed it to me, pocketed my money, and walked to the tram stop). The woman selling her old sewing machine. Or the other woman seated on a wooden crate, pouring cream (or borscht stock) through a funnel into empty vodka bottles. The liquid is so thick she has to pause every few seconds and shake it through the funnel neck into the bottles. These are the real stories of the street market.

I have taken from this market souvenirs aplenty (denim skirt for my daughter Kristin—“Pyramid Jeans: King of Desert, Best for You”—for $6.50; two old record albums, made in Poland, Buddy Holly and Billie Holiday, 35 cents each; three Polish fishing lures for Jack Hickerson—“If the walleyes won’t take your Little Cleos, Jack old Buddy, whack ’em with some of these Polski spinners”), but I have precious few photographs of those remarkable old faces, the faces out of National Geographic or Singer stories. Some time I would love to spend ten hours in this market with a telephoto lens and a dozen rolls of film. Those photos might be the best buy in the place, the real treasure of the street market.

Most foreign goods come to Poland in brightly colored, soft-pack plastic suitcases on trains, buses, and cars hauled by a small army of private peddlers. Poland-Berlin, Poland-Budapest, Poland-Prague and Poland-Turkey were the most popular trading routes in late 1989, although Polish Peddlers were famous all over Europe: Michelle’s friend Rafał Pniewski recalls being greeted upon arrival in Syria by an Arab inquiring in perfect Polish what he had to sell, and what he wanted to buy. A colleague recalls sitting in a Lot airplane on a flight returning from southern Ukraine, juice dripping on his shoulder from the bags of grapes stuffed into overhead compartments by his fellow passengers. Poles were in an especially favorable position to trade, because some quirk of the post-World War II settlement gave them visa-free access to West Bloc nations like Austria and West Berlin. The First Polish Peddlers Army operated in and around Berlin, the Second Army in Prague, the Third Army in Vienna. Stray battalions were scattered across the continent. Polish traders were, in fact, an international problem.

Unlike American salesmen on expense accounts, hard-core traders live as cheaply as possible while abroad. They sleep in tents or motor vehicles or sprawled on the grass. They bring their own food, living for weeks on boiled eggs, tea, suchary (thick, army-issue biscuits you have to karate chop to break), and tins of Mazowiecki paté (ground protein—and bone—with a hearty, dog foody aroma). Some even bring their own petrol. They undercut local merchants on what they sell, then bargain closely on what they buy. They thus produce minimal revenue for “host” countries. When they depart, they leave a mess. Germans and Czechs claim they steal everything too hot or heavy to haul away, although I have not known Poles to steal much from other nationals, except automobiles. The reason ordinary tourists can’t purchase a train ticket for Berlin, Budapest or Prague earlier than thirty days before departure is that peddlers would, if allowed, buy out all seats months in advance; and the reason they have so much trouble getting a ticket to Budapest, Berlin, and Prague later then twenty-nine days before departure is that peddlers have by then booked them out. (Perhaps it is for this reason that foreigners are sent to Orbis, but Orbis never, not once, produced a train ticket for me). On trains the peddlers cause headaches for conductors and customs people, who naturally become cynical, careless, contemptuous, and corrupt. The border between Czechoslovakia and Poland was a case study in mutual ill will, much of it the result of Polish traders. In late May of 1991, truckers blocked the German-Polish border crossing at Frankfurt am Oder, claiming they were being extorted by customs agents turned venal after dealing with too many Polish traders.

Peddlers are held in contempt by most Poles, who consider trading too undignified of a member of the lower nobility, too dirty for intellectuals, too suspect for peasants… although the greater community envies their wealth and has no qualms about consuming the goodies they bring into Poland.

Whatever difficulties Polish traders have caused for the heads of other governments, who must protect their various populaces, and for heads of their own government, who must negotiate visa treaties with Austria, Hungary, and the United Germany, they clearly constitute a re-emerging middle class. Professional peddlers piled up a good amount of money, and more is being made as prices rise even higher and a system of wholesaling develops. That this new wealth is not effectively taxed is the government’s fault, not the peddlers’. Who volunteers taxes he is not required to pay? The fact is, it’s the people who run risks—who in Gatsby’s words “see an opportunity and take it,” who spend the time in automobile lines at border crossings and the long hours riding train all over Central Europe—that reap rewards. And their rewards will increase. And their example will become an example to the Soviets in their tortured road to a free market economy. And, gradually, to Poles themselves, who must cease looking to America as a place where dreams can come true, and begin looking at Poland as the land of opportunity.