Ewa Bednarowicz looks out the tram window at the long queue of women in front of the milk store. “This trip is a journey into Polish history,” she says.

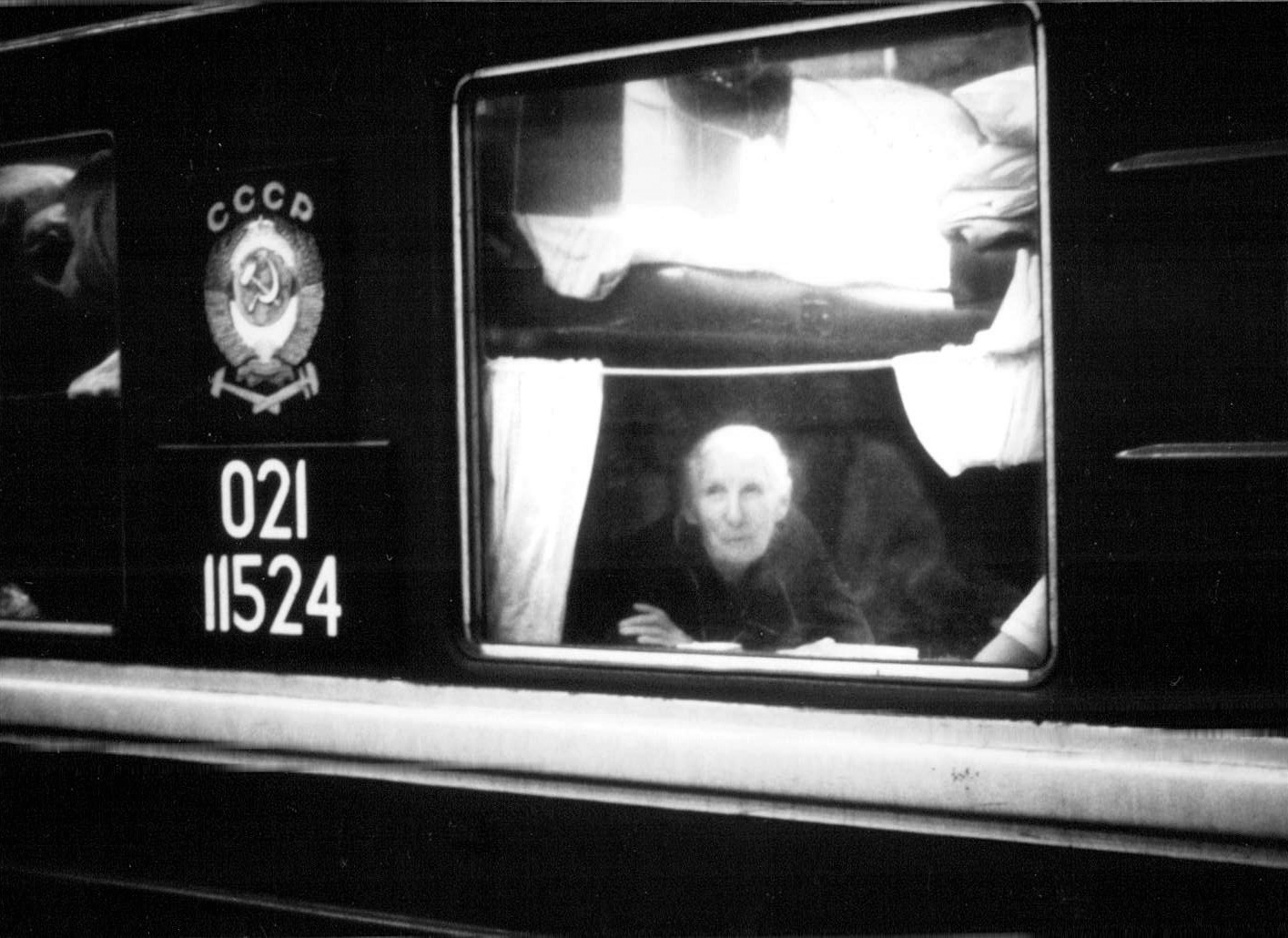

This nine-day excursion to Leningrad is costing Michelle, Ewa, Neil, and me 850,000 złotych each, plus $50 spending money, plus $40 hard currency for tourist visas. At the June 1991 rate of exchange, 850,000 złotych amounts to $70.83 . . . $70.83 each for second-class train travel Warsaw to Leningrad to Łódź—two entire days and one night each way—plus six days at a comfortable and quite modern hotel, double occupancy, with toilet and shower in the room, three meals a day, Polish guide for the entire trip and Intourist guides and buses to monuments and museums in and around the city. The souvenir money buys meals on the train at fifty cents a dinner, sheets and blankets for the bunks at eight cents a night, and Soviet champagne at one dollar a bottle. And souvenirs: T-shirts that read (in Russian) “Hard Rock Café, Leningrad,” several art books, Soviet army and navy gear, matrioshka dolls, hand-decorated wooden boxes, a six-poster poster of Lenin, a watercolor of the Neva River.

St. Isaac’s Cathedral is one of many surprises in Soviet Russia—a surprise that it’s still standing, a surprise that, like churches in Poland, it’s being carefully restored. Apparently religion is not dead in Russia either. St. Isaac’s took 500,000 workers forty years to build. Half of them died during its construction. Enormous columns of dark red granite on the outside, gorgeous intricacies of marble, lapis, malachite, and gold leaf inside. The oil paintings, now flaking, are being converted into mosaics at the rate of one square meter per worker per year. A cruciform with four symmetrical and very abbreviated axes, St. Isaac’s lacks the long nave characteristic of Western churches. St. Isaac’s couldn’t accommodate 15,000 workers, let along 500,000. St. Isaac’s is a monument for the nobility.

“During the siege of Leningrad, St. Isaac’s was closed but not vandalized,” our guide tells us. “You cannot eat gold. After the War, vandalism became a problem.”

She does not say at what expense this church has been restored.

On the evening of the longest day of the year, Ewa, Michelle, Neil and I gather a few bottles of Soviet champaign and head for the number 3 electric bus, intent on spending a white night beside the Neva, talking, drinking, watching ships, open to whatever adventure comes our way. As the bus makes its labored way through the cratered streets, Ewa falls into conversation with two middle-aged Russian women, both curious about the foreigners, both a little blitzed on vodka or cognac. Not ten minutes into our quest for adventure, we have been invited to midsummer night’s revels in the flat of two private Soviet citizens… well, at Sasha’s flat, but Vera will take us there while Sasha runs to fix maybe a bit of food with friends in the neighborhood. “You accept, comrades, our invitation?”

Accepting, we hop off the bus at the next stop and follow Vera to Sasha’s apartment, where she fumbles for ten minutes with the key—some kind of screw device foreign to us and, apparently, to Vera—until Sasha returns, half a dozen bagels in hand, and opens the door.

The fourth-floor flat is small: kitchen, living room, bath. The kitchen contains a sink and stove, on which Sasha sets to work immediately creating some kind of egg and tomato dish, with a couple of cans of fish-in-tomato-sauce served on the side. As she works, Vera entertains the guests in the living room-bedroom-dining room, seated around the small table or reclined on the bed in front of the color television, on which plays a Soviet version of Wheel of Fortune. This room—divided almost entirely in half by the refrigerator, wardrobe and vanity—is decorated only with Soviet girlie calendars (legs only, no bare breasts or behinds), and a team photo of some hockey squad. One shelf holds plastic lead soldiers and a few books, in Russian. Vera, half drunk, is pressing a little close to me, but I shift onto the bed, using Michelle as a screen, and she redirects her interest to Neil. The Wheel of Soviet Fortune spins, Soviet Vanna White poses, and the Soviet audience applauds politely. Sasha calls Vera to the kitchen, sends her back with a bottle of vodka, a real treasure since Gorbachev curtailed production (one reason he’s out of favor these days). The bottle is opened, drinks are poured, toasts are raised. Rejected by Neil, Vera returns to me, maneuvering around Michelle. “Russian men are hot and fat,” she says. A man from Leningrad wins the Wheel of Fortune competition and is eligible to win the final grand prize if he can identify a famous work of art by a Renaissance Italian painter. I move away from Vera. Ewa translates English to Russian, Russian to English, her fluency increasing with each shot of vodka. The man on the television selects the letters A and O, but they are not enough to allow him to identify Da Vinci’s “Madonna d’Litta.” The smile fades from his face as he sees his chance for the grand prize (a toaster oven) washing down the river. Sasha appears with supper. “He should have known it; it’s in the Hermitage Museum.” Sasha changes into a better dress for dinner.

Both women are divorced. Sasha has two children, “away at summer camp” right now. Camp, Ewa explains, might mean communist youth Pioneer Camp, or might just mean a summer cottage. Vera has no children, will never have children, a minor sin in the CCCP, which promotes Family almost as strongly as the Catholic Church. In her childlessness, she feels obviously inadequate and incomplete. For her there is no hope: short, dumpy, middle-aged, round-faced, no children, no man, only one vacation in her life, Bulgaria this summer, her first trip out of the country after nineteen years of work… ahead of her now only the downward slope of life after 40. Recently Soviet women have taken to advertising in the West: photos and resumés to magazines and newspapers, marriage brokers and underground networking, even expensive video-taped self-promotions aired on Western television stations. But Vera has no money, no looks, no youth. No possibilities.

Her affections fixate on Michelle. “I like you the best. I cannot say why. People just have tastes. I love you the best…”

For Sasha, perhaps more hope: she is slender, she has children, she is a boss in some factory in the city. She holds her vodka better. She worries about her guests, about what they will say about her, about her city once they leave. “Have you had enough to eat? Would you like some potato and fish soup? Please do not tell anyone how poor we are here. Tell them this is a beautiful city.” She circulates a photo of herself and her children.

Michelle deflecting Vera with toasts of vodka. Sasha telling Ewa about her job, her children, her ex-husband. Vera coming unraveled. On the television, some Soviet big band. Sasha obviously in the mood to dance, but both males ignoring her signals. A toast to peace, “the most important thing.” Vera in the kitchen, drunk and desperate for affection. Sasha knowing Vera is crumbling. Her guests beating a panicky retreat. “Things getting out of hand here.” “Who knows where we are, what could happen.” “Want to watch the police.” An exchange of addresses, promises to write—in English? in Russian?—and then four Westerners stumbling out the door, past the small winter coat of one of Sasha’s boys, quick, quick, quick down the steps, toward the street, Vera and Sasha waving from the window, shouting in English “We love you,” and the four of us waving back even as we run toward the tram, quick, quick, quick onto the tram, away from that dark Russian desperation, toward the chartered banks of the Neva, there to swill champaign beside the broad, accepting waters, and watch the bridges rise, and the freighters parade through, in a scene off some tourist painting or an Aurora Publishers postcard.

“Have you noticed,” I point out, “there is not a single banana or orange or grapefruit or lemon for sale anywhere in this city.” In Poland, bananas were the first fruits of the new capitalism. You found them everywhere after the country opened up, and people eating them everywhere. Exactly one banana’s distance from every street market, you found a trash can overflowing with peels.

But that was Poland.

“I don’t know how they live or what they eat,” says Ewa. “No salad, no cauliflower, not even cabbage and onions. Only cucumbers. Vera told me that tomatoes cost 10 rubles a kilo, which is unbelievable for these people.”

Meat, even sausage and ground meat, is scarce and bad. Cucumbers are indeed the only vegetable in plentiful supply. Lunch and dinner, every meal of our visit, it’s cucumbers, cucumbers, cucumbers. Our last day in Leningrad brings to the street market what appears to be the first hint of this year’s strawberry crop: maybe ten quarts. Long queues at the milk store. Empty shelves in the food stores—not even fruit juices, apart from strawberry juice concentrate. And certainly no kiosks on the corner selling hamburgery or hotdogi. Only ice cream on a stick, and coin-operated drink machines: deposit 15 kopeks, and get a glass full of watered-down sugar water. Leave the glass for the next customer, comrade.

The Russians are handsome and well formed, especially the males, but I don’t know how they live or what they eat.

Among “Things to Do During Free Time,” a sign in our hotel lobby lists theater, ballet, boat rides on the Neva, and souvenir stands at the semi-privatized, semi-policed Ostrovosky Square Market.

“Be careful,” the sign warns.

I have spent long hours among Russian traders in Warsaw and Łódź, in street markets from Białystok to Kraków to Berlin. I have found Russians to be more or less honest traders (occasionally they’ll slip you a half-empty jar of caviar or a dead watch, but keep your eyes open and your hand on your money, and you’ll be okay). I have seen interesting things for sale at this market. Also, we’d like to try our hand at trading some Western goods for Soviet souvenirs, especially a couple of shirts and blue jeans brought for that very purpose. So the morning of our fourth day in Leningrad, we are off to the market with a bag full of trading goods and a head full of plans.

And by golly, this works! First try, we trade a pair of just slightly worn American blue jeans for an English language souvenir book on Leningrad I had been wanting since we hit town, published probably at $2 or $3, but $20 the asking price all over Leningrad. For $20, I can get a brand new pair of jeans at Poor Borsch’s back in Minnesota, so this is a good trade.

Then we trade three Southwest State University T-shirts (the old logo, and that the reason the bookstore had marked them down to a couple of bucks apiece, but the Soviets neither know nor care) for a super hockey jersey, bright red, number 9, CCCP across the front, KPUTOV in yellow letters across the back. Michelle very pleased, and I as well.

Fending off peddlers of watches we don’t want and matrioshka dolls we already have, I move toward a display of lead soldiers, hand painted, for friend John Nemo and perhaps a few for myself. I’ve got a brand new pair of 501s, label still on, direct from the U.S.A., and how many soldiers you going to give me for this pair of Levi’s?

The lad looks them over, noting the stitching and location of the seam, the tag, the size. Then he offers me eight soldiers for the jeans.

Fifteen, I suggest.

Ten.

Ten soldiers and one of those ceramic pipes there, for Michelle. Ten soldiers and one pipe.

While he ponders my last offer, a couple of other boys come up behind us, offering hard cash for the jeans. I indicate I want soldiers, not cash, and return to bargaining with the vendor. The boys say something to him in Russian, but I can’t understand. “Ten soldiers and one pipe for the jeans.”

“I will sell soldiers only for money,” the toy soldier man announces. “Three dollars each soldier.”

I turn to the boys who want to buy the jeans. “How much?” I ask.

“Twenty dollars.”

“How many soldiers will you give me for twenty dollars?”

“Sell us the jeans, Mister. We give you twenty-five.”

“Ten soldiers and one pipe for $25?” I ask the vendor. He agrees.

“I’ll take your $25,” I tell the boys, “and give them to this fellow for the soldiers and pipe.” They count two tens and five ones into my hand, I give them the jeans, and turn to the vendor.

But my hand contains only five one-dollar bills. The two tens have vanished.

Michelle and I look at each other and say the same thing simultaneously: “Rip-off!”

“You go this way, I’ll go that,” I tell her. I’m off running, looking for a pair of brand new Levi 501s, a couple of young boys on the run, finding not a thing, stopping, angry, perplexed, feeling stupid and gulled, pushing ahead, knowing the chase is up and the hunt futile, hesitating, pressing ahead, returning, hesitating, angry, foolish.

Half way around the market square I meet Michelle.

Who has the jeans in her shaking American hands.

“Out of the corner of my eye, I saw them duck behind one of the vendor’s stands, and I followed them. One began to run, but the other just walked along. He had the jeans. I caught up and grabbed them. I think they’re the same ones.”

What a tough Western girl I have! “Son of a bitch!” I keep repeating over and over again. “You got the jeans.”

“We gotta get out of here,” she repeats over and over again.

Now it’s our turn: quick down Nevsky Prospect. Melt into the crowds. “We’ll take these jeans to the store that buys Western clothes,” I tell Michelle the Bold, sell them, and use the money to buy soldiers and a pipe.”

Alas, we’re not quick enough. A tug at my sleeve and a voice in my ear: “Hey, mister, how about my five dollars back?”

“What?”

“You have your jeans. Please give me my five dollars.”

“For two years I live in Poland,” I lecture the lad, two fingers raised for emphasis, knowing the old Russian-Polish animosities, “and for two years I have never been cheated by a Pole. I am three days in Leningrad, and already somebody tries to steal from me.”

“Please, mister, my five dollars?”

“Well, you’ve learned a lesson: don’t fuck with Americans, and especially don’t fuck with tough western American girls. Now get lost before I call a cop.”

At the Passage Store we negotiate a price of 500 rubles for the jeans. A Godfather type peels five one-hundred-ruble notes off his bankroll and hands them to me. This is another scam: fifty- and hundred-ruble notes, repudiated over a month ago, are no longer legal tender. “Nyet,” I tell the Godfather. No hundreds. Twenty-five ruble notes only. He chuckles amicably as he counts out 20 twenty-five ruble notes.

“Man, you can’t trust these Ruskies,” Michelle says.

Returning to Nevsky Prospect, we encounter Neil and Ewa, tell them the story of Michelle, Scourge of Market Pirates, share a good laugh, and send them off to the market to buy as many soldiers as 500 rubles will buy.

Which turns out to be sixteen. “Sixteen lead soldiers for the pair of jeans,” I tell Michelle the Avenger.

“Plus the hockey shirt, plus the book,” she reminds me. “Plus we have five dollars from those nice Russian boys.”

The museums and churches and palaces of Leningrad are impressive, as is the old brick building along the Neva where Stalin interred those who disagreed with or threatened him, as are the canals and the river itself—but the most impressive things in Leningrad are its monuments to those who died in the 900-day blockade of World War II: the Memorial to the Heroic Defenders of Leningrad on Victory Square, and the mass graves of the Piskarev Cemetery.

Especially the cemetery, where 470,000 soldiers and workers lie buried in mass graves, rectilinear mounds arranged in long rows, each headed by a stone bearing the year in which these people died, the number of the mound, and a star for soldiers, a hammer and sickle for workers. The mounds number over 200, and the grass grows lush on each of them. An eternal flame burns at one end of the cemetery, a stone memorial rises at the other.

Most of our company is too hung-over for cemeteries, but Ewa and I want to see this place. Our visit coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the Nazi blockade, an occasion for parades and a wreath-laying ceremony. Ewa and I stall until noon, chatting with our Intourist guide and one of her older comrades, a medal-encrusted survivor of 78 who claims to have co-founded the Pioneer camp to which every East Bloc teenager aspired. Our guide’s deference and respect suggest his story is legitimate, as do his medals: row upon row, more medals than stars or hammer and sickles on grave mounds. The old Russian affection for medals never died.

Just before noon, he excuses himself to join the parade of mourners marching down the central aisle between the green mounds. First, surviving veterans and children of the blockade. Next, representatives of political organizations, followed by military organizations, party representatives, foreign representatives—China, France, even Germany… but not the U.S.A. A dozen Orthodox priests with a large white wreath. Then the people, anybody, everybody, people with a single red rose or a red carnation, for the mounds, for the memorial, for trees near some of the graves. A great river of people. The amazing capacity of the Slavic people to sustain suffering, the great anonymous masses of the Russian folk.

To one side, a demonstrator with a hand-lettered sign: “I did not die during the blockade. I am dying a little bit at a time now.”

I spent most of the train trip through Poland toward the Soviet border trying to figure a good place to hide my illegally purchased rubles, settling finally for a pocket hollowed out in the end of my couchette mattress, where the cover had been ripped, probably by somebody else making a pocket in which to stash illegal rubles. I improved on his plan slightly, twisting the cover off to one side and making a second pocket, in which I deposited my 1,000 rubles, then twisting it back into shape, so the old pocket would act as a decoy . . . then turning the mattress upside down in its sleeve, tearing a new hole and making yet another dummy pocket… all of which proved needless precaution, as the customs agent searched neither mattress or luggage, asked only about gold and pornography.

Most of the return trip I spend worrying about customs agents confiscating the champagne and vodka we are bringing with us, anxious lest I lose the Soviet sailor’s cap and army belt I’ve bought as souvenirs for Ensign Stephen Pichaske, wondering whether I should have bought that $150 nineteenth century icon at Ostrovsky Square. And talking and drinking and eating with Ewa and Neil and Michelle. And looking out the window at the potatoes, more potatoes, and yet more potatoes grown in small private garden patches along the railroad tracks. And drinking tea made from water heated at the coal-fired boiler at the end of our sleeping car.

On the return trip, we fall in briefly with a young soldier from Kazakhstan en route to assignment in Dresden. He speaks no English, of course, but is quite taken with one of the Polish girls on the tour (also with Michelle and Ewa) and by the idea of being among Americans and Brits. We offer him some champagne, which he drinks without enthusiasm. “True Soviets do not drink champagne,” he informs us. “True Soviets drink vodka. Would you like to drink some Russian vodka?”

Ewa and Michelle, old hands at vodka drinking, accept enthusiastically, but our soldier has no vodka to drink. He can find some, however, and off he goes, up and down the entire length of the train, searching for good Russian vodka for his Western acquaintances, who meanwhile suck away at their good Russian champagne, becoming in the process increasingly drunk and just a little loud. One passenger complains, is offered a cup of champagne, and turns us down cold: “Soviets do not drink champagne,” he informs us gruffly.

Around 12:30 the soldier returns with a bottle, which he presents to us.

We open it, pour some in a cup, and drink, not tossing shots properly, just passing the cup around. But our soldier refuses his turn, and his refusal fuels our paranoia. So does our guide’s warning: “Be careful. Something is up.”

We consider our position: four Westerners alone in the amplitudes of the CCCP, suitcases loaded with souvenirs and Western clothing, purses and billfolds still thick with hard currency. The Soviet sleeping car has no proper compartments. no doors to lock before falling asleep, only a whole car full of ostensibly snoozing Soviets, some possibly playing bird-in-bunk, just waiting for us to get good and drunk so they can pull some slick stuff. Possibly the soldier himself is a Merry Prankster.

Our suspicions grow when he ducks back to his own bunk, then returns with a bag full of what smell like drug-laden balls of this or that, offers them around, again with vodka, again refusing to partake himself. “Be careful. Something is up.”

The upshot of the whole paranoia trip is that we refuse to either eat or drink, at which the disappointed soldier returns to his bunk and sleeps soundly, as we do not, until dawn. Daylight reveals the drug balls to be goat cheese. The vodka was a good-faith offer, we decide.

To restore Soviet-American relations, I offer him a T-shirt in English—“World Fencing Championship, Denver Colorado, 1989”—before we leave the train at Brest.

Crossing the Soviet-Polish border is the all-time slickest thing I have ever seen, a stroke of genius on the Polish guide’s part, and—like the tour itself—a fortuitous conjunction of strategy and the blind luck of catching the CCCP at the confused moment of its collapse. Half a year earlier, the entire tour would have been impossible, or, if possible, would have been tightly

controlled and closely guided. Half a year later, the tour would have cost ten times the price we paid, and been twice as dangerous. Sometimes you get lucky. A month earlier our egress from the CCCP would have been an agonizing twelve- or twenty-four- or forty-eight-hour nightmare peopled with huddled, smelly, hostile masses and surly, truculent guards. Sarah, Jim, others at the Institute had tales to tell. A few months later—who knows? Maybe easier, maybe tougher. Maybe duties and inspections. Maybe confiscations. Maybe delays. We have none of them. We have seized a moment, and it is ours.

Russian-Polish border crossings, everyone in Łódź understood, take so long that trains generally rolled out of Brest without their passengers, who disembark, squeeze into a large and crowded customs hall, ooze ever so slowly through inspections, emerge after eight or ten or fifteen hours on the other side of the fence, to meet the next train to Warsaw. Thus, while trains from Moscow are usually only an hour or two delayed, passengers arrive in Warsaw twelve to twenty-four hours delayed, and on a train different from the one on which they left Moscow. The crises at the crossings are a direct result of new Soviet freedom of travel—more people going in and out—and the arrival of The West at Russia’s very doorstep. No longer insulated by Poland and East Germany, and Russia now shoulders alone the burden of policing East-West trade and traffic. And she’s hopelessly unprepared.

The resultant crush of traders and tourists overloads the system, producing legendary waits: five days in some cases, many kilometers of trucks, cars, and buses at the motor vehicle crossings, which number only six.

Mindful of this, our tour guide has formulated a plan: take the train to Brest, take a taxi to the crossing point, walk across the border, and meet Polish tour bus on the other side of the line.

Which is exactly what we do. Outside the Brest train station, we hire six Soviet taxis to carry us to the actual border crossing, past 2.5 kilometers of waiting tour buses and trucks and automobiles, as close to the gate as the drivers dare to come. We pay them, shoulder our luggage, and walk a hundred meters past more cars and buses toward a gate in a cyclone fence. Our Polish guide explains that we were on foot, and the gate opens. We pass through, carrying our luggage, arriving half a kilometer (and hundreds of additional cars and buses) down the road at a second gate. Here our guide speaks to another Russian guard, and again the gate opens, and again we walk west, another 200 meters, past more cars and buses. To yet another gate.

At the third gate a problem develops. This guard orders us to queue with others: members of other tours, car owners, Russians in vehicles loaded with trading goods. No special treatment here. As we are well within sight of a large customs hall and the actual border, most of us would be more than willing to congratulate ourselves on having jumped perhaps four kilometers of people and wait out turn. But our Polish guide is not satisfied. She returns to the second gate, brings her man to the third gate, and passes with the second and third guard into the customs building. I study the people around me: Russians camping out in tents, families cooking dinner in a stew pot over a fire made of cardboard boxes, people in various states of distress, anger, boredom, despair. Not a single west-bound vehicle passes through, although several east-bound vehicles exit, headed for Brest and Moscow.

Eventually our guide returns, and collects our passports (those of the Westerners on top, please), handing them to a guard who disappears into the building. We are permitted to pass through the third gate, walking our luggage past more cars and buses, to the front of the building. There we wait, barred who from the twisting gravel road through Russian-Polish no-man’s-land only by a couple of young army guards with light arms. We speak loudly in English and glance nervously at our watches: the guide’s story is that the Americans have to catch an international flight out of Warsaw.

After half an hour, two Belgian cars pass the auto inspection on our right—which includes driving over a grease pit from which guards can inspect the underside of vehicles—and speed down the gravel road to Poland. A tour group from New Zealand comes up beside us. Their bus crosses the grease pit. They climb inside. “Could you hold the bus for us?” our Polish guide asks; “We’re going only to Polish customs.” Scorning us peasants on foot, they zoom off the road toward Mother Poland and the West. Our guide asks one of the soldiers about renting a bus to take us to the Polish station. 80 rubles we could pay. No, he thinks, this would not be possible. We will have to walk.

“How far?” somebody asks in Polish.

“One kilometer,” the soldier answers in Russian.

“One kilometer?” I repeat in English, thinking I have misunderstood. “Only one—not two, not three?”

“One kilometer.”

“Then we will run,” I say in English. The soldier smiles.

Still we wait, an hour, the New Zealanders gone ahead of us, and the Belgians. Finally our guide calls one of the soldiers over, goes with him into the customs house.

Ten minutes later, she returns, with guard, with passports, with permission to move on. “We go now,” she says brusquely, and quickly enough the whole group hoists their luggage, walks gingerly past the bemused soldier, and heads down the winding gravel road to Poland. Goddam! We are out of Russia, and nobody but nobody has once examined our luggage. I could be hauling five icons. I could be hauling ten kilos of Soviet gold, fifteen kilos of Ukrainian Red. Anything. Everything. Nobody even looked.

Michelle and I rifle our passports looking for a red “CCCP” egress stamp. Nothing. “Westerners don’t get stamped,” Ewa tells us. “You didn’t get stamped coming in, either.”

“Unfair,” Michelle objects. “Let’s go back and demand our stamp.”

“Keep walking,” I suggest tersely. The toy soldiers and the books are heavy, and the sun warm.

Around the first bend in the gravel road, a curious sight: cars and buses backed up, as outside gates one and two and three.

“Nothing is moving here,” Michelle whispers. “Something’s going on at the Polish border too.”

The Polish word for “strike” passes back and forth among members of the group, but we just keep walking, past cars and buses, more of them now, past the Belgians, past the New Zealanders in their comfortable bus, to the Bug river, to an armed guard in front of a red and white striped crossing barrier.

“Passports,” he demands as we approach.

I hand him mine.

“No stamp,” he points out.

“Americans are not given stamps,” I tell him. Unsure of himself and certainly unwilling to assume responsibility for a decision of this magnitude, he confers with a colleague in the sentry box. “Westerners are not given stamps,” his colleague confirms. The guard phones his superiors. Finally he shrugs his of shoulder, raises the gate, and the whole tour group goes trip, trip, tripping over the bridge, toward a Polish guard on the other side of the Bug.

“Polska Tour,” our guide smiles. With a wave of his hand, the Polish guard motions us through his barrier, examining not a single passport, not a single piece of luggage. Past more parked vehicles we walk, toward the Polish customs shed, where, after a ten-minute pause (apparently the Polish guards are on strike), we walk on through, past cars, past buses, to the back of the building. Where waits—yes!—the bus from Łódź.

And that is the story of the Polish tour group that just walked across the border at Brest—three hours flat, ahead of all the queues of Russian cars, on Soviet citizens, Intourist tours, New Zealanders, Belgians. They are waiting there still, for all I know. A happy bunch indeed, of Polish and American and British tourists, headed back to Sweet Home Łódź with disco tape blaring over the bus loudspeaker.

“Once at the German border last year, a friend and I waited two days,” a Pole tells me. “It’s good we had Westerners with us.”

“It was good at the Polish border that we had Poles along,” I responded.

“The line of cars to get into the Soviet Union is 17 kilometers long,” the bus driver announces on the loud speaker.

Then a second announcement: “We will pick up a group of traders headed for Łódź. I met them earlier today and negotiated with them for a ride. Thirty-five people. Please, everyone on this tour sit in front of the bus.”

Well, why carry sixteen when you can carry fifty-one and make extra złotych on the side?

At the train station we meet the Russians and their guide, loaded with suitcases, tired, anxious, having endured heaven knows what to get this far, delighted with this bus which will bring them to the Promised Land, wary of Poles and Americans, confronting, most for the first time in their lives, The West, here, now, on this bus, a little sooner than they had expected.

Carefully they load their bags, press watchfully into the rear seats, stare forward at us. They are tired, but also alert to possibilities. Not two kilometers on the road one member of our tour has bought a Zenith camera for seventy Deutschmarks, hard currency. Other Russians offer watches, sweatshirts. One girl shows me a silver and gold bracelet: “Twenty dollars,” she says in English. Michelle holds up the hockey jersey: “Does anyone have one of these?” (She wants one more for John Nemo, Dean of the College of St. Thomas, a former player himself, a peewee coach, and in fact the Minneapolis-St. Paul coach of the year).

No hockey jerseys. The lead soldiers will have to suffice.

A “Perestroika” watch?

None: perestroika is history, and so are perestroika watches.

There is bartering all up and down the bus, and later off the bus when it pauses in Warsaw for kiełbasa and beer. One Russian has already sold his chainsaw, and the girl with the silver bracelet is approaching everyone in sight. I feel a curious adopted national pride, showing Poland off to in-coming Russians, an emotion apparent as well in the other Poles. Welcome, comrades, to the West, land of plenty, bananas in the streets and all the good beer you can drink. Even easy conversion into hard currency.

I buy the bracelet for $10 American.

This is indeed what the Soviets have come for. “They get only one chance usually,” their guide says, “and they have unbelievable trouble: trouble getting visas, trouble at the borders, trouble on the trains, trouble in Poland. Poles and Russians do not like each other, as you know. Each knows a truth about the other which neither admits, not even among themselves. These people get cheated and robbed in Poland, by customers and by the host families they stay with. None speak Polish. They don’t even know the currency. They have only themselves to help each other, and they are all afraid. But the hard currency they bring home will pay half a year of expenses in the Soviet Union.”

“This sounds just like Poles only a year ago,” says Michelle to Ewa.

“How Poland has changed,” Ewa exclaimed. “This trip has been a journey back in time.”