“It was so much easier then,” she says wistfully, eyes bright with remembrance but just a hint of weariness in her voice. “There was only here or there, and you knew where you had to be.”

She is Docent Dr. Agnieszka Salska, Director of the Institute for English Philology at Łódź University, author of several articles and an important book on Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press. She holds the highest rank a Polish university can offer—and she is a former member (some have used the word “big shot”) in Solidarity. Today on a walking tour of Solidarity Łódź she remembers the old days.

“Because of martial law, you could be detained without arrest and without charges. Detainment lasted maybe a year for most Solidarity activists. Since there were no charges, there were in effect no ‘political prisoners,’ although one of the things we were constantly trying to do was get them to admit the fact of political prisoners. Even those formally charged with breaking the law were booked on normal criminal charges and treated like common criminals: made to work, housed with other criminals, sometimes beaten. Two leaders of Łódź Solidarity—Andrzej Słowik and Jerzy Kropiwnicki—started a hunger strike in prison for the recognition of the rights of political prisoners. Słowik was force-fed. I think it did him some permanent harm, although he is back in office as the head of Łódź Solidarity today. He was released in 1986, in the amnesty, after four and a half years in prison for appearing in the window of the Łódź Solidarity building on the morning of December 18, 1981.”

In the early days of martial law, travel was restricted. You could not travel from Łódź to Warsaw without official permission (shades of life in Nazi Poland); troops blocked the county borders (students living at home often crossed such borders on their way to school each morning; some moved to town and lived with friends, I have been told). “Two of our men went to the December 12 meeting in Gdańsk. Almost everyone there was arrested as they left the meeting, except Słowik and Kropiwnicki. They made it home somehow, but were arrested the next day.”

Parish priests communicated news about prisoners to family and friends, administered relief to the prisoners’ families, provided a rally point for sympathizers and members of Solidarity. In Łódź the so-called “Solidarity Church” was the Jesuit Church—formerly the Evangelical church—three blocks from the English Institute. Sunday mass provided an opportunity for Solidarity people to congregate legally. The sermon, on an appropriate New Testament text emphasizing human rights, would drift back and forth between theology and politics, always implying more than was stated explicitly. Being a priest in such a church was dangerous, although those who put themselves in danger in the early eighties are much admired today. “Last year our priest, Father Mieczykowski, received the City of Łódź award,” Dr. Salska says. “It wasn’t too long ago we were signing petitions to keep him here.”

In front of the church stands a large wooded cross towering over a marble slab commemorating another priest, Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, a modern Polish martyr, one of the unfortunate ones. The inscription reads “14. IX. 1947—19(?). X. 1984.” “He was not a strong man,” Dr. Salska remembers, but he had a driver who also functioned as a body guard, ex-special forces in the military, a very agile man. Both men were driving one night to Warsaw when their car was forced to the side of the road. The body guard managed to roll out of the door of the automobile which had picked them up, and to escape. Another vehicle was coming by, and the milicja could not turn around and get him again. He got to a church, where he told everyone what happened. He was kept in hiding for quite awhile, the only man who could identify the assailants. There were prayer vigils in churches all over Poland.”

“Was Father Popiełuszko ever found?”

“A few days later the body was dragged out of a pond behind a dam. He had been badly beaten. We all knew what had happened and who had done it.”

Terror and intimidation were the tools of the milicja. “They always went for the young men. They were told to ‘get the young ones, get the men.’ It was part of the intimidation.”

Of course there were forged documents and propaganda as well—Solidarity was the enemy of the people. “I was once shown a list of individuals Solidarity supposedly wanted to get rid of,” Dr. Salska recalls, “a list I was supposed to have helped put together. It was all nonsense, designed to confuse you.” Usually it backfired: writing in the Warsaw Voice, Krzysztof Jasiewicz noted, “In the days of the communist propaganda,… because the Communists were portraying someone in a bad light, the public knew that that person was probably very decent.”

The soldiers, recalls Dr. Salska, herself a mother, were pretty young too, and she admits to having felt just a bit maternal toward them. “They were not from Łódź; the boys from Łódź were sent to other areas. And they were frightened too. Scared little boys with these big guns!”

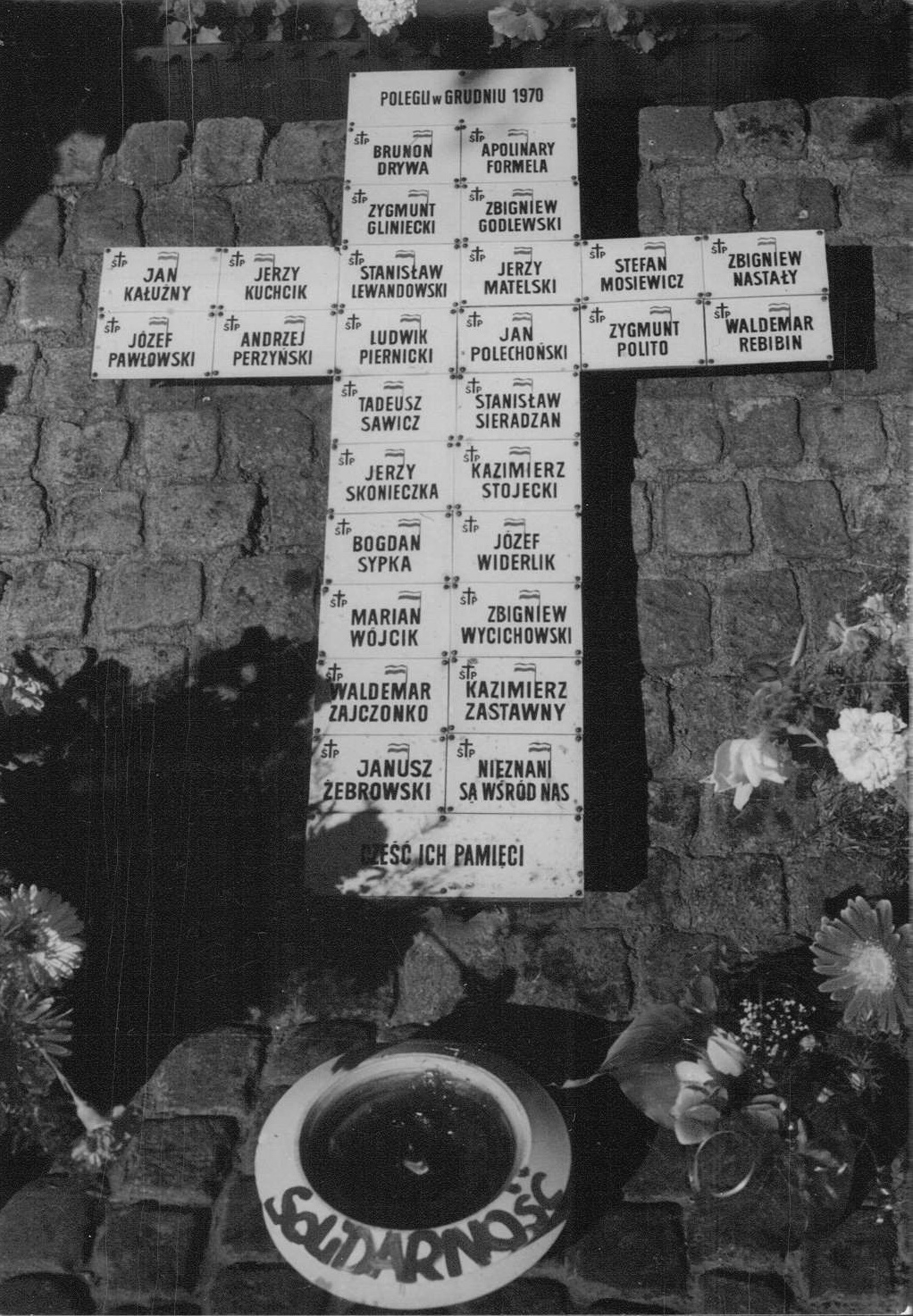

We walk to Holy Cross Church, oldest in the City of Łódź, to another remembrance, this one of the Gdańsk Uprising in 1970: a small slab commemorating those who died in that action. After martial law, the tablet—set in the outside wall of the Church, eight feet off the ground—became a rallying point for Solidarity members. “We held our small protests here, our public rallies. Men would be up there in those windows taking photographs. We would smile, wave…”

“The tablet was not removed by authorities?” I ask.

“It was attached to the Church, you see, so removing it would have been… more difficult.”

“And the photographs? They must be tucked away in some files. Where are the files now?”

“Oh, I am sure they are around somewhere,” she smiles. (I recall having seen pictures taken at the Jesuit Church by a Solidarity photo-journalist in an album I bought at the Gdańsk Shipyard souvenir booth).

Although I can’t imagine the Polish Roman Catholic Church needing strengthening, its position was enhanced by association with Solidarity, even during the early 1980s. “The position of left intellectuals became untenable after martial law. The Catholic position was all that was left. There were many conversions then. I don’t mean to be cynical. They had nowhere to go. Many members of the new government are Catholic intellectuals, including of course Prime Minister Mazowiecki, who was one of their best writers and editors.”

Explicit Church support for Solidarity came mostly on the parish level. “When the Pope visited Poland, he met with General Jaruzelski [then in charge of martial law, later President of Poland, with Mazowiecki his Prime Minister], not with Wałęsa or other Solidarity people. They talked for an hour or more. I remember being in Warsaw, waiting for the Pope to come out and bless us, and the meeting went on and on. We all joked: ‘Jaruzelski is making his confession; he needs plenty of time.”

The goal of Solidarity during the early eighties was, first and foremost, simply to survive. Second, it sought to make things not work as a protest against the denial of basic human rights. Leaders were identified, detained and—after their release—monitored (making contact with them dangerous to others in the movement). New leaders emerged, people with new ideas, new programs. Then they would be identified and detained… and replaced as leaders. “Continuity was difficult. And we always worried about informers.”

“I must tell you one story,” she says. “On the first anniversary of the suppression of Solidarity, we were having a small rally at the Institute. It was on a break between classes, so the students would not be inconvenienced, and the rector—who was our elected rector and should not have too much to answer for—was present, and naturally the secret police showed up, and right in the middle of things who walked in but a group from the American Embassy, Fulbright representatives and all. Elizabeth Corwin was there; she will remember. I don’t know what they wanted, and I’m sure they didn’t know what was going on, but the police were furious. ‘This is an international conspiracy,’ they raged. We kept hearing that one for a year.”

“You yourself were permitted to leave the country during the early martial law years,” I remind her. This was 1983, when Dr. Salska spent time in Philadelphia working on her Dickinson-Whitman book. “Were they trying to get you out of the way?”

“That is a funny thing,” she answers. “I had applied for the scholarship in 1979, and been turned down, so I thought I would reapply for the program. This time I was accepted. When I requested a passport for travel to the West, both for myself and for my son, I was turned down right away. I reapplied, of course, and they asked all sorts of questions. There were telephone calls and more visits. What they wanted me to do was identify some leaders for them, admit I was one myself. When they realized I was not giving them what they wanted, the harassment continued. But by then it was just intimidation.”

“I remember one time, they said, ‘Well, why don’t you just admit it: this is only an excuse for you to escape from Poland.’ Then I decided—and I remember quite consciously making a decision—to make a big scene. ‘I am a serious scholar,’ I shouted at them, ‘and my work is important work.’ On and on.”

Then, with no explanation, just a few weeks before the start of fall term, the passport was granted. “I have no explanation,” she admits, “except total confusion. Or perhaps I had a friend somewhere I did not know about. Sometimes I feel a bit guilty, as if maybe I did not do enough. I just don’t know.”

Throughout our conversation, I have been remembering my own student activist days during the high sixties: the demonstrations, the rooftops lined with government photographers, the files, the government agents. I remember demonstrations and sit-ins at Ohio University during my graduate school days. I remember learning that my immediate predecessor at Bradley Polytech had been let go essentially because he was advisor to the SDS. I remember one member of Bradley SDS telling me that he and others returned to Peoria from the Port Huron Convention to discover that in their absence they’d been dismissed from the school, no reason given, no appeal permitted. I too felt guilty for somehow escaping jail, staying in school to the Ph. D., taking Harry’s job, ending up finally as a department chair and a full professor. Maybe I too did not do enough.

I have been remembering too the collective mind of other sixties types, and one of Dr. Salska final comments strikes a very familiar chord. “There was something quite romantic about it all in those early days, a kind of game we were playing with the police: keeping secrets, avoiding arrest, rescuing our people when they got caught, supporting each other, spiriting people away in the dark. I remember when one of our people in Warsaw was shot and had to be hospitalized: it became a game of springing him from the hospital. And we did it. It was like, ‘Hurrah, that’s one more for our side!’

“Things were so much simpler in those days, and I worried a lot less than I do now.”

A smile crosses her face, a golden glow of battles fought and remembered victories, and I realize consciously something I have subconsciously suspected for a long while: Docent Dr. Agnieszka Salska, Director of the Institute of English Studies, is just another one of those sixties people who made good.