The three steel crosses that comprise the Gdańsk Shipyard Monument rise through brick pavement deliberately fractured, as if to suggest three towering steel flowers thrusting irresistibly skyward from some great organic bulbs buried deep in the Polish soil. Rough a their bases as dried, husky stalks of corn, they smooth as they rise to streamlined shafts as graceful as the prows of oceanliners. At the crossbeams, a hundred feet in the air, three steel anchors hang like three crucified Christs, underscoring the metaphor of death and resurrection, of life triumphant. On the faces of the various shafts, representations of the Polish spirit, figures a little drawn but neither suffering tragically nor triumphing heroically, just working Poles doing working things like cleaning the yard, welding a ship. Around the perimeter of the monument, memorials to the dead in the 1970 strike for a five-day week, victims of the 1981 imposition of martial law, and other Solidarity martyrs.

The monument is a striking monument to one of those glorious moments in human history which are at once both tragic and magnificent. It was the striking shipyard workers themselves who decided, in the summer of 1980, to build a memorial to the dead of a decade before. They decided on the memorial one day before they formally organized a strike committee to formulate a list of grievances, and a week before the first appearance of the newsletter Solidarność. The monument was completed four months later, with steel appropriated from the yards, in temperatures well below freezing. In December 1980 a celebratory mass was said at the partially completed monument. In January 1981, martial law imprisoned workers and sympathizing intellectuals and supportive clergy alike. The Gdańsk shipyard workers had built a monument commemorating themselves.

In the dining room of the Grand Hotel in Sopot, a resort city just north of and contiguous to Gdańsk, broiled salmon with boiled potatoes, salad, cooked asparagus or cauliflower, and a Polish beer costs less than ten dollars in spring 1991. A flaming ice cream and fruit dessert adds another dollar. The food is served on porcelain plates, pink or white napkins at the side, by suited waiters who are professionals. A three-member band, possibly Hungarian, in folk costumes provides live guitar, violin, and accordion music: classical compositions, folk dances, songs from “Fiddler on the Roof” and “The Fantastics.” The violinist’s eyes glisten like a gypsy’s.

From the dining room itself, high-ceilinged, all aqua and white and turquoise, diners look out through broad glass windows at the aqua and turquoise waters of the Baltic Sea, toward ships anchored in the bay, toward the long wooden pier that projects far into the Baltic, toward Hell on the peninsula 25 kilometers in the distance. At night, lights on the distant shore glimmer and are gone: ganglia of lights that are ships headed out to sea move serenely across the waters. During the day, especially in high season, vacationing Poles pack the beaches and the pier, turning Sopot into a kind of Atlantic City of the Baltic. Many camp along the shore; the more adventurous defy posted warnings and swim in the polluted waters. A few join the Marina, where they can swim in indoor pools, or play tennis, or shoot pool, or bowl.

Once, in the old days when university-provided documents allowed us to pay Polish rates instead of prices for “visitors from communist countries” or “visitors from capitalist countries,” when hotels were empty anyway because it was very early spring… once in the old days, Michelle and I stayed a weekend at the Grand Hotel in Sopot, for $4 a night. It was the most elegant weekend of our lives: a room of enormous space, hardwood floors, fourteen-foot ceilings and tall doors with silver handles opening onto a balcony overlooking the Baltic. We thought we were in New Haven, Connecticut in 1927. I half expected Jay Gatsby and Daisy Fey to walk into the nearly empty dining room.

Gdańsk took World War II pretty much on the chin, and most of the old town here, like Old Warsaw, is restoration. The main difference is that Warsaw got razed to the ground, while Gdańsk crumbled to eight or ten feet above street level. All the quant old buildings along Długi Targ—Landeshütte Strasse in the days when Gdańsk was Danzig—are restorations, as are City Hall, the Swedish wharf crane, the Jantar Hotel, and the churches. Photographs in the City Museum show Gdańsk just after the war, and a visit to the interior of any church will suggest just how much of the wall surface, roof, and furnishings is restored or new. Look carefully at the carved parapets on the old homes along Długi Targ, Mariacka, or Chlebnicka, especially from the back side, and you can see they have been pieced together like jigsaw puzzles from fragments left after wartime bombing. Many restored buildings display photographs of ruin and various stages of restoration, including the triumphant moment when an ornate metal dome, all multiple bulbs and filigree spires, was hoisted atop the church tower.

Still, the restored Old Town of Gdańsk has a magic unmatched by Warszawian restoration or even Krakówian originals. Its spires reach with a Scandinavian lightness not often found in Poland. Especially in the off season, when a visitor has these enchanted streets mostly to himself, when the purveyors of tourist paintings and amber souvenirs have quit the streets and gone home, when the restaurants are closed and the Jantar is empty. In the early morning hours or the gathering twilight of a winter Sunday to walk from the entrance gate at the head of Długi Targ down to the old moat is to walk through a dream landscape. Then Gdańsk is, with Kraków, Budapest, Paris, Berlin and Prague, one of Europe’s great old cities.

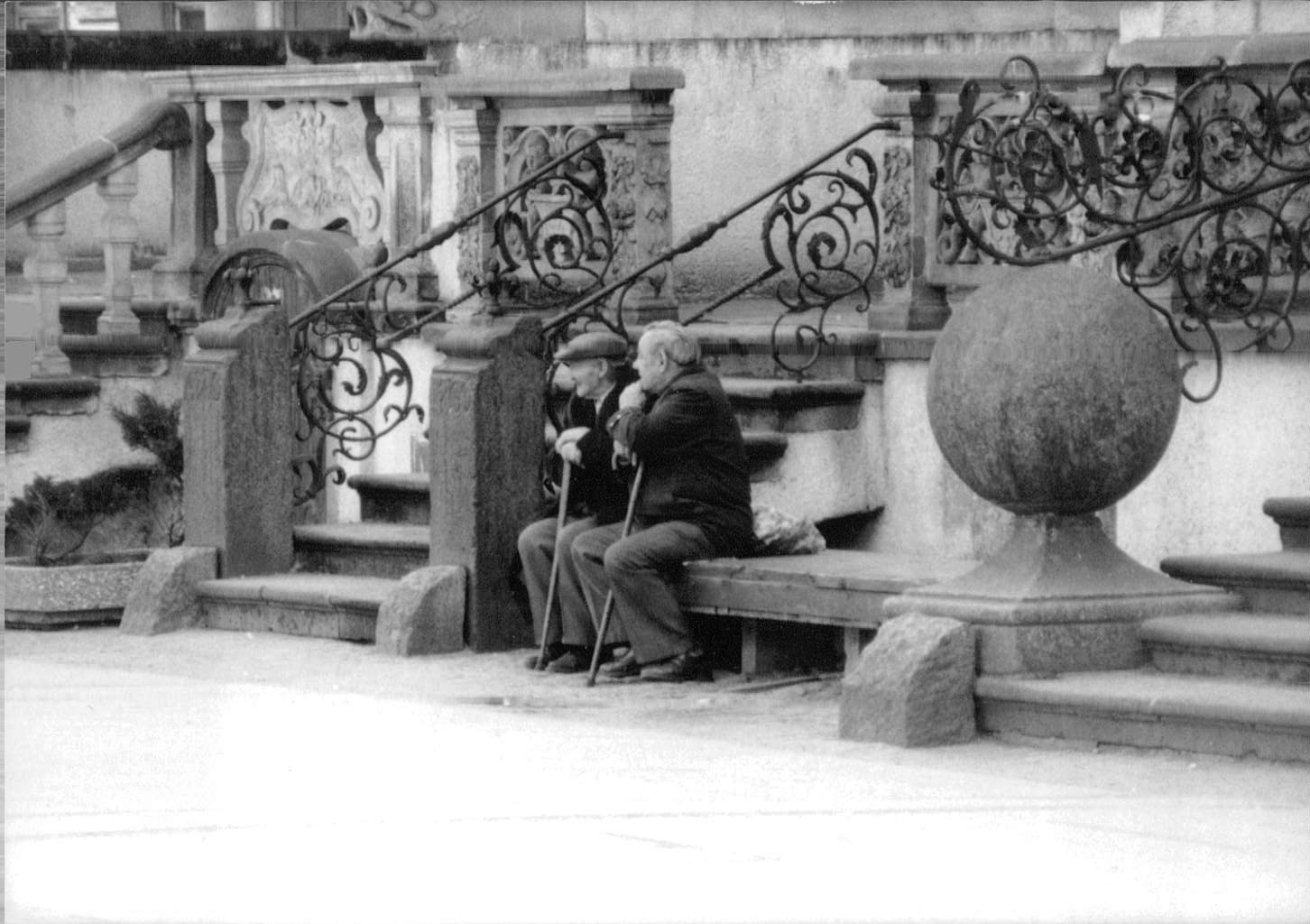

The old train station, Gdańsk Główny, tidy, elegant and light. The waterfront, and two yachts sailing Soviet flags. The underground café, in what used to be the crypt of an old cathedral. The indoor market, full of stalls selling meat, clothing, souvenirs, perishables—and vendors outside selling fruits and vegetables, flowers and meat and fish. The small parks nearly downtown, with fountains and benches. The statue of Neptune on Długi Targ. Sections of mediaeval wall, including one fourteenth century tower which now houses a photo processing operation. Street musicians in the summer: violinists, guitarists, somebody playing Bach’s “Toccatta and Fugue in D Minor” on a Premier vibraphone. Sidewalk stands and glamorous shops specializing in amber and silver, come in, take a look, very good prices, $40 buys you an art nouveau brooch, $150 a string of rounded and graded amber beads, $2 an amber heart for your girlfriend. Wear amber to mitigate arthritis pain. Wear Amber to ward off sickness. Distill amber in alcohol, take three drops daily on a spoon of sugar, and you will stay forever young…

Checking into the Poseidon Hotel, a man with a stack of złotych three inches thick. The top bill is a 500,000 note. A pool game these days costs 15,000 and a small drink of wine 16,000. The loveliest of lovely Polish women drift like barracudas through the lobby, nostrils alert to the smell of foreign currency and passports.

In Old Town, on ulica Minogi, one of the back streets, the church of St. Jana, a building that has not yet been restored. The wooden gate in the fence surrounding the church is open, and the side door to the church as well, an oversight, perhaps, on the part of workers intent on getting home this Friday afternoon. Through the yard choked with weeds, piles of cement bags, and heaps of bricks and blocks I slip inside the building like a ferret.

A thicket of scaffolding above, piles of rubble below. The walls have been rebricked, and the ceiling closed over. The underside of the ceiling in the chancel area and transept has been plastered and painted, and frames for new windows are in place. The rest of this fourteenth century building, however, is still in post-War ruin: bashed altar, columns stripped to bare brick, facing stones in a heap in the transept. In one aisle, on makeshift wooden shelves, assorted fragments of carved limestone, jigsaw pieces yet to be fitted together, fragments of an altar or tomb or decorative facing from the building itself. On the altar, half an inch of dust and small debris, and pieces of the old altarpiece: the raised arm and hand of Christ, the head of some disciple or onlooker, a bit of drapery or ornament. In the floor, the pulverized grave slab of some long-deceased bishop. Probably his bones have disappeared as well, for the earth has been dug out below the slab as vandals, unable to break through the top, dug around and under. The tomb of one Nathan Schroder is also mostly rubble: one of the stone decorative statues lies, at present, in front of the basalt and marble sarcophagus—or what remains of the basalt and marble sarcophagus. Funny things can happen between burial on 12 July 1638 and May 28, 1991… and this mischief, Herr Schroder, is the work of your own countrymen.

Well—in a few years, St. Jana’s will be as restored as St. Mary’s on Długi Targ, where tombstones are also reconstructed fragments. Herr Schroder’s grave will be quite as lovely as Mary’s altar. The bones, and whatever this man took with him to the tomb? Dust in the wind, spoils of war, a lesson on the vanity of all sublunary life.

The huge cranes of the Gdańsk Shipyard—now no longer the Gdańsk Shipyard Lenin—are idle much of the time these days, perhaps to the benefit of greater Poland, since vessels produced for the Soviet Union were not always a net economic credit. “We built them beautiful ships,” one of the old timers explains, “filled with expensive electronic equipment, just what they ordered, usually things we had to buy in the West. And the ship would be delivered on time, guaranteed for one year, the ship and everything on her. After 364 days, she would be back in Gdańsk, and you would not recognize her: all the electronic equipment gone, and other machinery too, anything that could be removed. A shell of a vessel. ‘So where is all the equipment?’ we would ask.

“‘Well, it was not working, so of course we had to remove it. It needs to be replaced with equipment that works.’

“‘That was the best equipment, we got it from Sweden, from Germany. Of course it works.’

“‘No, comrade, it was not working.’

“‘So where is the broken equipment? We cannot replace it if we do not have it. Maybe it can be fixed.’

“‘I have told you, comrade, the equipment was not working, so we had to remove it from the ship. Now you must replace it.’

“‘I will have to call Warsaw about this matter.’

“Then we would call Warsaw, and they would say, ‘Tak, tak,’ the ship is under warranty. Replace all that expensive equipment for our Soviet comrades.”

Up the coast from Gdańsk, contiguous with the resort town of Sopot, is Gdynia, Poland’s major port city, filled with cranes in docks and repair yards. Many vessels came to the Gdynia yards during the winter of 1990-91 to escape the storm gathering in Suez, some to be refitted for service in the North Sea. Many vessels fly the colors of old East Bloc trading partners of Poland: sailors on a freighter from the People’s Republic of China once invited Michelle and me to tour their ship after we had walked, unchecked and unchallenged, directly into the repair yard docks. (Wary of being literally Shanghaied, we settled for exchanging a few Budweiser Beer patches for a People’s Republic pennant, and congratulated ourselves on contact with the Far East). Many vessels fly Western flags: Gdańsk and Gdynia have always been more cosmopolitan than the rest of Poland, and therefore less isolated, and therefore less easily deceived about realities of life in the East as contrasted to life in the West.

To the south of the repair docks, on a long pier off Washington Street, a string of museum ships: the three-master Dar Pomorza, built in Hamburg in 1909; a naval ship, the Błyskawica, built in the United Kingdom in 1937; and even a Belgian ship, the Bouesse, built in Tampa, Florida. The Polish Yacht Club headquarters are on the opposite side of the pier from the Dar Pomorza. Ice cream and U.S.A. Popcorn is sold everywhere along the pier. A crazy motor vehicle gussied up to resemble a pirate ship offers free rides. Young couples stroll arm in arm toward the sailors’ memorial at the far end of the pier, and on a fine summer Sunday afternoon there are more lovely Polish girls in Gdynia than at the Poseidon Hotel or on the boardwalk in Sopot.

One hour southeast of Gdańsk is Marienburg, now Malbork, home of the Teutonic Knights after their eviction from Hungary and a subsequent invitation by the Duke of Mazovia to subjugate the heathen Prussians. That was after 1226, and before a series of wars, starting with Grünwald in 1410 and culminating in the absorption of Order territories into Poland-Lithuania in the middle of the fifteenth century. A huge heap of brick and cement, much of it dating to the high middle ages, Malbork is under almost constant reconstruction and is one of the great mediaeval castles of Europe. As Poland opens increasingly to tourism, Malbork becomes increasingly touristed, and prices have risen accordingly. On my first visit, Michelle, Allen Weltzien, and I found the castle closed, and paid a guard one thin U.S. dollar to let us inside. On our second visit, Michelle and I paid about a dollar apiece admission fee. In spring of 1991, ticket prices have risen to two dollars, tours of the museum section with a tour guide only… English-speaking guides, $18 a whack.

Still, Malbork is a bully sight—all one would expect of a complex that at any given moment could host 500 monks, 500 priests, and 500 knights, plus 1,000 servants—and one more reminder of the incredible layered richness of Polish history.

St. Brigid’s, Gdańsk, is less impressive than Malbork: a small, rectangular structure with a modest tower, eclipsed in every architectural way by neighboring St. Katherine’s. The interior of St. Brigid’s lacks the old ornaments of most other Gdańsk churches: a small fragment of decorated plaster wall; an oil painting by Herman Han, 1612, of the assumption of St. Brigid; another oil painting on the arch of the right aisle, God the Father receiving the body of Christ, borne up from the tomb by a pair of angels; a grave slab on the left aisle of the nave; and the carvings of Christ, St. Mary, and St. John, high above the nave. St. Brigid’s looks like any one of a hundred, of a thousand smaller churches scattered all over Europe, a church with some small history and some small art, a church battered by the War, a church renovated after the War into simple functionalism.

Increasingly, however, St. Brigid’s is ornamented with art of a different nature: pine, iron, steel, brick. St. Brigid’s is the Solidarność Church, where shipyard workers met and demonstrated and prayed during the 1980s, where in the 1990s national mass is celebrated on important Polish holidays. Its memorials are to the Polish dead of World War II, to the officers murdered at Katyn, to Solidarność priest Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, to the heroes of the struggle of the 1980s. In such a context, it is somehow appropriate that pews be modern, functional, uncarved working-class pine. That confessionals be clean, simple, unadorned boxes. That light fixtures be basic iron, and walls, like the factory walls of Łódź, be working-class brick. That at least one of the side altars be shipyard steel, and the grillwork around the altar in front of the right side aisle be black wrought iron. That the iron art on the rear balcony resemble figures on the Shipyard Memorial: drawn, gaunt, hard. In such a place, workers can still come to pray and meditate—workers and those who remember the years of struggle now too much forgotten in the New Poland.

If the simplicity of this place causes tourists to pass St. Brigid’s lightly by, perhaps so much the better. Keep it quiet, keep it holy.