I entered Poland in September of 1989, and returned to the United States in August of 1991. During that two-year period Łódź—and the rest of Poland, and the rest of the old East Bloc—was transformed and retransformed three or four times over. Change continued after 1991, and change continues today. ’Tis not, sir, the same country with which I fell in love… although it was, and remains a place I love and, in some small measure, know.

The meditations of this book reflect the Poland Michelle and I knew: inflation, political chaos, economic reform, the shifting face of Piotrkowska Street. Throughout 1992 and 1993 Polish friends provided periodic updates: letters, phone calls, visits. For longer or shorter stays, Michelle and I hosted both Tom and Ewa Bednarowicz, Agnieszka Salska, Agnieszka and Grzegorz Siewko, Agnieszka Leńko, Anna Kępa, Ella Tarnówska, and Ewa Ziołańska. We drank a lot of vodka, talked a lot of stories, ate a lot of crabs’ legs.

I returned to Łódź in December of 1991 and, most recently, in December of 1992. My habit has been to land in Berlin, then take a train from Berlin to Łódź. A round-trip flight Berlin-Warsaw adds one to two hundred dollars to the cost of an international ticket, several times the price of a second-class train seat… and the Berlin lay-over allows time for a bottle of wine with Gabriele.

The Berlin Wall is a thing of the past in December 1992, little more than a long and winding path through the heart of the city, used at some points as a park, at some points as a garbage dump. Michelle thinks it would make an ideal bike path, but land in this city is too precious. Already Siemens and Sony plan a huge joint-venture building on Berlin Wall no-man’s-land near Brandenburger Tor, and despite all that newly added emptiness in eastern Berlin, other sections of the no-man’s-land will inevitably be developed. The crossing at Friederichstrasse, where Michelle and I and several thousand other people stood like impatient cattle in 1989, is a museum these days, and both S-bahn and U-bahn run smoothly east to west, north to south, along the tracks of a unified city. I saw the Wall go up, and I saw the Wall come down, I reflect in early December 1992 on a river walk between the arrival of my airplane from

Minneapolis and the departure of my train for Warsaw. I remember Kennedy’s speech and the Berlin Airlift. I am becoming one of the Old Ones, and Gabriele too. Sic Transit whatever.

At Hauptbahnhof I buy a train ticket from Berlin to Kutno: $25 one-way, second class . . . still cheaper than plane fare, but I can’t help feeling nostalgic for that first round-trip ticket Michelle and I bought in 1989 for a couple of bucks total. One corner of the station, on the lower level by the mostly vandalized lockers, retains the old ticket windows for eastern destinations, signs in Russian still, washed out photos of Soviet landmarks on the wall, even a dead tourist bureau behind one open door. The old yellow East Bloc furniture, the old yellow East Bloc wall paneling. Tales of things past, of things passing.

$25 isn’t the end of the ticket business, however. My train to Kutno (junction with the north-south Polish rail which will take me down a short leg of the triangle to Łódź) is some kind of new Berlin-Warsaw super-express. It has a proper name and number—the Berolina, EC #43—and proper printed schedules lie on each seat. The carriages are brand new in all acceptable yuppie colors: teal, beige, plum. The lavatories are clean and toilet-paper equipped, the train includes a dining car and refreshment carts, and we are On Time right down the line. Formalities of the Polish-German border crossing are accomplished, most graciously, with the train in motion by officials who board in Frankfurt/Oder and leave the train at Rzepin, its first stop in Poland. A survey, printed in four languages and collected somewhere around Poznań, solicits suggestions for further improvements in service and equipment. During the five-hour ride, at least half a dozen service personnel enter my humble second-class compartment: purveyors of refreshments, passport inspectors, collectors of survey responses, conductors German and Polish.

Such service requires reservation and a surcharge as well, collected en route in marks and złotych. My Berlin-Kutno train ticket costs, finally, about $40. Second class, one way.

“Welcome to the new New Poland,” I think, wondering if maybe I should not have flown directly to Warsaw.

At Kutno I have exactly sixty seconds to get myself and my suitcases off the Berlin-Warsaw express. The Berolina arrives and departs almost before I disembark, nearly blows me right off the platform as it hustles on down the line. At the Kutno ticket window I request a one-way, second-class fare to Łódź, a distance of maybe fifty kilometers, offering in payment a 10,000 złotych bill, about one dollar. “No, no, sir,” says the clerk; “not enough these days.” She shows me the ticket: 11,200 złotych, second class, one-way.

Well lackaday: this slo-mo ride on a battered double-decker used to cost mere pennies, kopecks, groszy, centimes. Used to be, used to be: the days of riding PKP rails are gone for good. Those were the days, my friend… You may be back in Poland, but it’s 1992.

Notes on the new New Poland? How about Casino Łódź for starters, main floor of the Centrum Hotel opposite Fabryczna Station: mirrored walls and potted (plastic) plants, a couple of bars, slots, blackjack, piped-in disco music and strobe lights, dealers in black tuxedos with white ruffled shirts, the loveliest of long-legged Polish lovelies skating across the smart black-and-white expanses, glitz and glitter, noise, flash, cash, bash . . . virtually empty. “It’s losing money like crazy,” confides a student who works there; “it attracts almost no foreigners. But for the moment, the wages are very good.”

Seriously now, would you trust a Polish gambling operation?

Along Piotrkowska Street, more Polish than ever. Part of the street is a walking mall finally, and dressed to the nines this December for Christmas. Colored lights and plastic trees. The bedraggled Santa Claus in a dirty red suit and scuzzy white beard handing out trinkets in Central wouldn’t fool my dog Bear. New ownership at Hortex translates roughly to same delicious ice cream, same deluxe service, double the price. Mercedes and BMWs line the streets around the Grand Hotel. Rooms cost $100 a night (when you wake up in the morning, you’re still in Łódź), the restaurant and café are full of foreign businessmen sweet-talking smart, young Polish women. For a dollar and a half, one of those young boys outside will hand wash the Polish mud off your car while you linger inside.

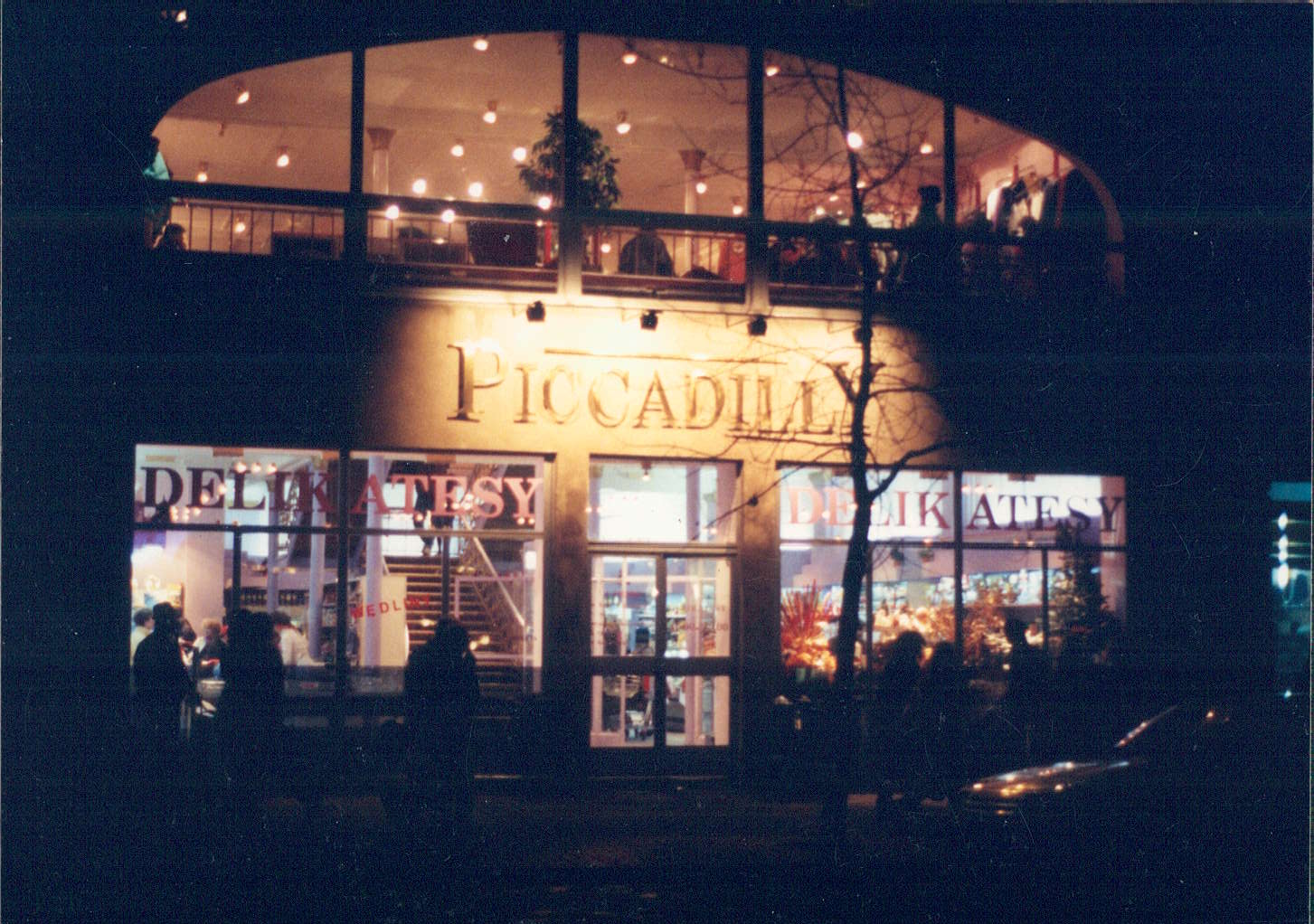

The Golden Duck is packed; you need reservations to get in, and even reservations are no guarantee. “When first the Golden Duck opened, Michelle and I often dined there alone…” Rainbow Tours, now in swanky new offices, is also packed; Grzegorz, Sławek, and Agata have no time to talk now. The frozen foods store, where you could always, even in the darkest days, get packages of frozen strawberries and frozen cauliflower for fifty cents a kilo, has become a new restaurant, one of a dozen along this street, all British-American cheap and cheerful: tile floors, plastic tables and counter in red and black and white, clean plate glass windows, microwaved burgers, gyros, fish and fries. The hamburger window at 56 is just another window, no burgers and no commemorative marker. Fashion stores are everywhere, and jewelry shops. Piccadilly and Argentum. Leather skirts and jackets in Central now run 75% of American prices, maybe 100%. Bargains in crystal, cloisonné and porcelain, on anything imported from Russia or China. Łódź is still the best shopping in Poland, in terms of goods and prices. But Łódź is no longer free. Not on Piotrkowska, not on the side streets and parallel streets. Not anywhere.

Two years ago Bob Jones and I walked down Piotrkowska one afternoon. “In four years, we won’t be able to afford this street,” he told me.

Tram service has been further reduced, the price of tram tickets is up another notch. A Łódź-to-Warsaw, second class train ticket costs now nearly four dollars. Seventeen cents round-trip when I came to Poland. The 50% discounts for state employees will end soon. Automobile and truck traffic is a problem during peak morning and evening periods: rush minute traffic in Łódź. Things will get worse before they get better.

In the book stores, translations of Harlequin romances side-by-side with Dostoevsky and Hemingway. “I just finished translating a biography of Michael Jordan,” one fifth-year male at the Institute tells me. “It was terrific!” The hottest book going is a kiss-and-tell exposé written by a French journalist who balled her way through the whole Polish legislature before doing a strip-tease in print.

I visit the bread store: same as ever. Some things are forever. The public market is more structured but lively as ever; seeing the boxes of puppies I hear again the voice of Michelle: “Somebody’s got to save these puppies.”

Agnieszka and Piotr Salski have found a new Chinese restaurant in Łódź, better than the Golden Duck, somewhat removed from Piotrkowska Street, but quiet and clean and nicely decorated with a goldfish pond and oriental graphics. Mario’s pizza in the Polonia Hotel still serves the best pizza in Łódź, in the most authentic American fifties pizza restaurant atmosphere.

Hamburgers? Anywhere. Everywhere.

Agnieszka Salska and I make a one-day excursion to Warsaw: small business at the Fulbright office, mostly chat. Coffee and cake in the subdued elegance of the old Victoria Hotel Café, Berlin of 1958. The Russian street peddlers have been evicted from the square around the Palace of Culture, relocated “elsewhere” in the city. There’s nothing here now but a small village of permanent wooden sheds—Polish-owned and licensed and selling mostly clothing—and a more or less permanent carnival. The old Party Headquarters on Jerozolimskie now houses the Centrum Bankowo Finansowe. Why not? Ground floor of the Palace of Culture had been converted into an indoor shopping mall long before Michelle and I left. In one bank, a cash machine.

In Old town Warsaw, tourist and prices approach levels of London, Berlin and Paris. No art bargains here, or even souvenir bargains. Wood carvings, prints, paintings, woven wall hangings, amber, silver, greeting cards made of dried flowers: so many lovely things. I buy nothing, grieve inwardly for the old days of solitude and low prices. Even the churches are crowded. On the steps of the old cathedral a Western tourist in pleated slacks is stopped by a native, who objects to his ice cream cone: “No food in the church. You may not enter this place eating ice cream.” In a thick New Jersey accent, the tourist shouts ahead to his wife: “Go on ahead, Shirley; I’m sick of all these goddam churches anyway.”

During lunch at the Bong Sen, a British pop vocalist complains to her agent about the Polish royalty offer. Two Austrian businessmen talk joint ventures with one Polish colleague. A can of Canada Dry tonic water costs a dollar. Lunch for two runs nearly twenty dollars, and not as much food, methinks, as in the old days when Michelle and I ate here together, two bucks the pair of us, including two bottles of generic Polish tonic.

Warsaw now has car dealerships for Ford, Chevrolet, Porsche and BMW. In Warsaw every hour is rush hour.

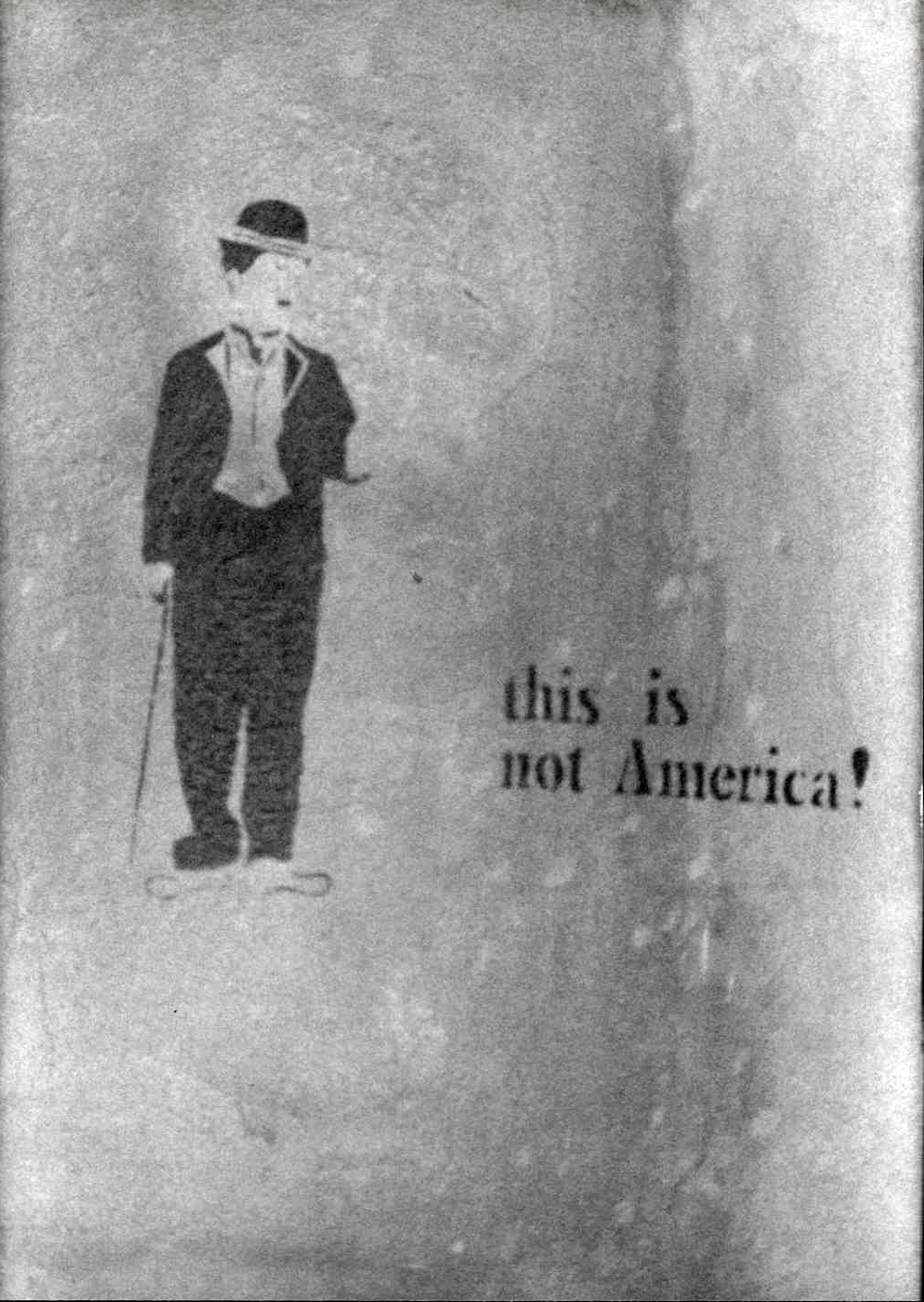

Agnieszka Salska, Roman Catholic, hard-core Solidarity member with a Ph. D. in American literature, mourns the “westernization” of New Poland, the new materialism, the harsh economic bottom-lining, decline of “old values, old culture, old traditions.” She frets aloud over church incursions into state, especially on the areas of education and abortion rights. She worries about the old folks, about Łukasz now in Poznań, and about growing old herself. “When your parents start to go, you realize you’re next on the edge.” There is little joy in watching one’s self become, gradually, inexorably, one of the Old Ones.

I visit Poznań, hosted by Łukasz Salski and Iwona Kozłowiec. Łukasz treats me to the opera, Iwona to a student party in a fifth-floor downtown loft. Knock at the door, tell them Marek sent you. Tall windows set below tall ceilings, white lace curtains, white paint on the walls, mattresses on the floor, the only real furniture a stereo system and speakers. Wine, vodka, and my bottle of Lithuanian champagne. This used to be “Soviet Champagne”; the very label is a cultural artifact. We sit on the floor propped against a wall. The music is mostly cool jazz. Tobacco and marijuana. Couples disappear into the recesses of the flat, reappear after five or ten minutes. American beat, 1962. Iwona, a fifth-year student at the Philological Institute, is writing her thesis on Henry Miller.

Łukasz still drives a Syrena. His flat is decorated with kerosene lanterns. He makes me a present of two all-metal model cars, produced in Russia, the good ones, two models I did not have, including the big black stretch limos beloved of old party bureaucrats. “A friend from Russia stays with me when he comes to Poland to peddle these,” he explains. “He will not mind if I give you two.”

One afternoon on the way to her flat, Iwona announces that we must detour to the “school” where she “teaches”: the European Correspondence School of Foreign Languages, a few offices in one of the upper stories of an old Poznań factory. Its operational center is a room perhaps forty feet square, two walls of which are taken up by shelves supporting 120 or 130 cardboard boxes, each bearing a name, each filled with envelopes. The names on the boxes are the correspondence students’ teachers—Kozłowiec reads one box—who read their weekly assignments, correct and grade them, add a personal comment or two, seal them in self-addressed stamped envelopes, which return to this office for counting, certification and mailing. Iwona does not know what students pay for their correspondence work in English; she receives 3,000 złotych, about twenty cents, per lesson corrected. Each course consists of 32 lessons, and there are many levels and courses. The correspondence package includes workbook, exercises, a tape, and “your own personal tutor.” Iwona is personal tutor to maybe five hundred correspondence students.

“This is a terrible way to learn English,” Iwona admits. “The lessons are simple translation or substitution exercises: ‘Change the verb to the present tense.’ ‘Make the singular subject plural.’ ‘Substitute the correct form of you for me.’ Nobody ever checks pronunciation. This is no way to learn English.

“But it’s a very good way to make money. I earn about a hundred dollars a month. It’s useful at Christmas, and for buying books.”

This more than anything else strikes me about Poland, 1992: English is everywhere. It’s the smart language. Everyone wants English, everyone needs English . . . and people who can teach English are in great demand. My former students, despite their complaints, lead good lives these days. Anna 22, newly married to a medical student, complains in her new flat—fresh paint, parquet floors, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves filled floor-to-ceiling with books—about needing a new car. Agnieszka and Grzegorz, 23, newly married, complain about his inability to find work outside of their clothing-manufacturing business, and about living still in a dorm. About having traded the newer car for an older model . . . to underwrite their three-month trip through the States last summer. On their TV, we watch several hours of videotape, taken with their own camcorder. At the moment, Agnieszka is making big bucks giving private English lessons at the school where she teaches: classes she organizes, which she teaches, for which she collects. She’s grumpy that once these classes approached the $200-a-month level, the school raised their room rent.

Magda, 22, complains about a job offer somewhere in the east of Poland: the flat which comes with the job is attached to the school, a part of the school, not a separate building or a flat in some separate blok. “It would be too noisy,” she thinks. Her starting salary would be substantially more than that of an experienced biology teacher, who pays for his own flat, because she teaches English and the school needs English.

Beata is unhappy because translation contracts pay so little and the work is so long. “Ink is where you find it,” I tell her, thinking back to my early twenties dining on rice and chicken wings in a frosty graduate school apartment I shared with two other guys, $25 apiece a month, a now-demolished hovel behind the Maple Shade Inn across the street from the Athens, Ohio Airport.

Who do these kids think they are, anyway?

1993 American students, I guess. “We’re not supporting education these days,” our university financial aid officer once told me; “we’re supporting lifestyles.”

Or perhaps they’re just Poles, pessimistic and insecure as always. “Nobody expects this to last,” Agnieszka tells me. “I have plenty of work now, but tomorrow—who knows? Nothing has ever lasted very long in this country. You get what you can while you can.”

Okay. Things change, and things do not change. Some things survive all change. Sometimes the more things change, the more they stay the same. In Poland as in the rest of life.

“What do you think of the New Poland?” everyone wants to know. In two weeks, I am asked the same question a hundred times, and at the end of two weeks, I still have no answer. This country has aged a decade in slightly over a year.

So what do you tell your former lover, meeting her again ten years after the great affair?

“You look great, haven’t changed a bit. Same old you, same old me. Nothing could ever change, could it?”

Is that what you tell her?

“I’m happy for you, pleased things worked out so well for you. I wish I could have been part of your new prosperity.”

Is that what you say?

Do you play her a song? Ray Charles, “I Can’t Stop Loving You”? Dire Straits, “Romeo and Juliet”? Sinatra, “Thanks for the Memories”? Bob Dylan, “A Simple Twist of Fate”?

Is that what you do?

I guess. Mostly, I think, you thank her for the good times neither of you ever expected to last, for the good times locked safely away in both your hearts and in the vault of time-space eternally present. For the silly, irrelevant, insignificant scenes which, for whatever silly and irrelevant reason, have come to rest comfortably on the cupboard of your mind, polished to a platinum luster by the buffing cloth of time. For sanctifying a place, to which you can return, by time-struck gifts you cannot reclaim.

You thank her mostly, and bless her, and praise her ripeness, and promise she will stay forever young.

Well. She was very beautiful, graceful as a willow and fine-featured. She was dressed stylishly in black and white. She smiled when I waved, but turned her back quickly as I raised the camera. Then she disappeared into a blok of flats.